Published by 'SOVIET ANALYST'

(Editor and Publisher Christopher Story), Vol. 21, N. 9-10, 1993:

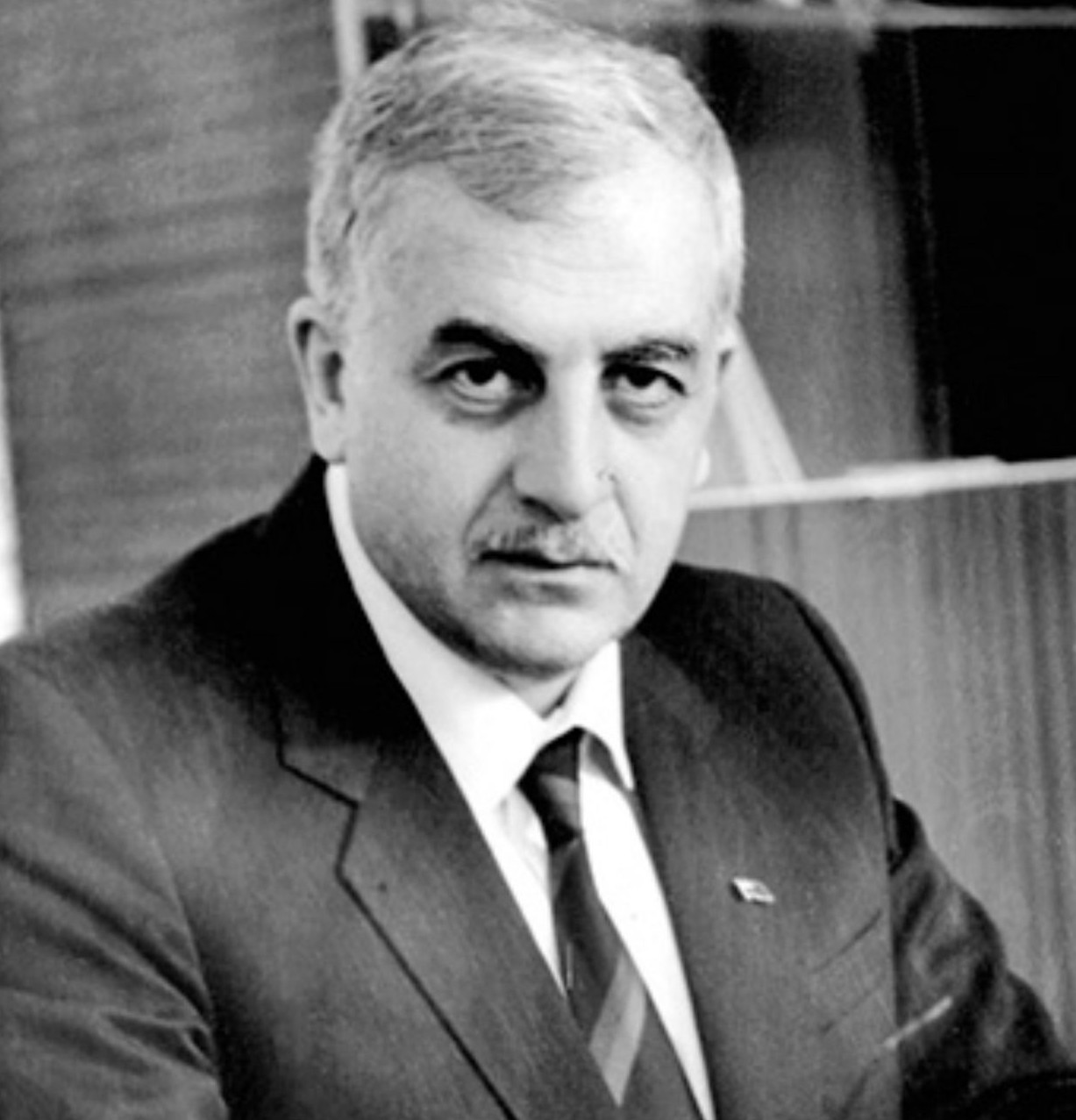

'Zviad Gamsakhurdia, the Legally Elected and Legitimate President of Georgia,

Describes the Evil Revenge of KGB & the Nomenklatura'

Preface of 'Soviet Analyst'

In the following exclusive dispatch to SOVIET ANALYST, Zviad Gamsakhurdia, the freely elected and legitimate President of Georgia, explains how the long arm of Moscow intervened in the affairs of Georgia and prevented the realization of the people's wish to be fully politically independent. He describes in anguished detail how this plot was implemented, and the key role played in it by Eduard Shevardnadze, in response to the requirements of Yevgeniy Pnimakov, head of the so-called Russian Foreign Intelligence Service, a manifestation of the KGB. The first sentence of this remarkable report is of exceptional importance to understanding events in Georgia, and also more broadly throughout the USSR. Gamsakhurdia writes: 'From 1987 onwards, through out the Soviet Union, 'democratic' and national liberation movements were activated'. The last two words reveal that, as Anatoliy Golitsin has explained in this service and in unpublished Memoranda seen by the Editor of this service, the 'democratic' and national liberation movements were not spontaneous, but controlled - via the Komsomol and the KGB - by the Soviet authorities. At least, that was the intention. In two of the Soviet Republics - Lithuania and Georgia - there rose to positions of leadership genuine anti-Communists and patriots. In both countries, the Communist/Nomenklatura networks have been restored. The West has cynically collaborated with Moscow in confining Georgia's fate, to which this issue is specially devoted.

National liberation movement, 'liberalization' and 'perestroika'

From 1987 onwards, throughout the Soviet Union, 'democratic' and national liberation movements were activated. The rulers of the USSR, realizing the impossibility of continuing with the Cold War, yet not deviating from their intention to retain their Communist Empire, embarked upon a period of apparent changes and 'liberalization' under the label 'perestroika'.

Simultaneously, despite the freeing of political prisoners, they continued their bloody repressions against the national liberation movements, especially in Vilnius, Tbilisi, Baku and in other centers. But in the face of the pressure exerted by the peoples' will and by world public opinion, they were forced to permit non-Communist elections to take place in certain Republics - a step which led to Declarations of Independence by these Republics and subsequently to the total disintegration of the USSR.

Elections

In Georgia, the national liberation and democratic movement achieved its ultimate triumph on 28th October 1990, when the country's first multi-party democratic elections were held. This was truly a bloodless revolution - in which Communists were obliged to hand power over to the democratically elected Parliament and Government. For the first time in 70 years, Georgia began to enjoy all the normal democratic freedom - a free press, political freedom, and religious freedom.

It is a serious error to imagine, as some still do, that the Soviet Government based in the Kremlin, and their local Communist associates, surrendered in Tbilisi without a struggle. Following the drastic, punitive measures of repression they had taken on 9th April 1989 against the national movement, they realized that their efforts had been in vain; so they lost no time in organizing a fake opposition - buttressed by powerful groups of armed criminals (the so called 'Mkhedrioni' gangs) which had been legalized by the Communists for emergency use.

They 'legitimized' this opposition by means of the creation of a so-called ' national congress', the members of which were 'elected' by means of false elections, and which was brought into existence for the sole purpose of replacing the true opposition, conducting political warfare, and committing acts of terrorism against the true national movement. In parallel with these measures, the Communists activated criminal extremists in so-called 'South Ossetia', who embarked upon a campaign of repression and terrorism against the local Georgian population, ruled directly from Moscow by the KGB and the Politburo.

By activating these forces, the Communists' intention had been to prevent truly democratic elections taking place in Georgia. However a combination of civil disobedience, mass popular demonstrations, protest actions by students and, finally a railway strike, compelled the Communist authorities to permit proper elections, in which the Communist Party participated.

Following the defeat of the Communists' cynical efforts to prevent elections taking place, the Communists suffered a humiliating defeat in the elections themselves, which were overwhelmingly won by State the 'Round Table/Free Georgia' grouping under my leadership. Faced with this outcome, the Moscow-based Communists and their associates in Tbilisi immediately set about preparing to reverse the course of events, enlisting the assistance of the mass media for this purpose.

Propaganda War

With effect from the very day of my election as Speaker of the Georgian Parliament on 14th November 1990, groups of criminal 'Mkhedrioni' gangs embarked upon a campaign of attacks on police stations and atrocities all over Georgia, while the fake 'national congress' tried to organize acts of protest against my legally elected Government. In Moscow, a group led by Shevardnadze, Popkhadse, Mgeladse and other renegade Communists formed a special staff dedicated to the task of overthrowing the legally elected, legitimate Government of Georgia - organizing for the purpose an unprecedented propaganda campaign directed from Moscow and carried throughout the entire world for the purpose of discrediting it.

The US Administration generally - and the US President, George Bush, and his Secretary of State, James Baker, with whom Shevardnadze had direct relationships, personally- strongly supported this cynical disinformation campaign against the legally elected authorities of Georgia, which had every intention of seceding from the Soviet Union and had as its main objective the establishment of an independent democratic state.

For its part, the Western mass media repeated in full the elaborate lies of Soviet propaganda - including the propagation of an image of myself as a cruel dictator of Georgia, a kind of Saddam Hussein of the Caucasus, who was engaged in the outright suppression of all personal freedoms, the arrest of political opponents, the wholesale violation of human rights, the oppression of national minorities, and the waging of 'fascist war' against them under the slogan 'Georgia for the Georgians'.

The reality was the exact opposite of the evil picture painted by this Soviet propaganda. A total of 25 newspapers in Georgia systematically criticized and slandered the President and Parliament, an activity for which they were not persecuted (unlike the treatment they would have received under the Communists). The so-called 'opposition' was granted an 'alternative hour' on State Television, and my Government even offered these people the possibility of opening an independent TV channel. Since absolute political freedom was permitted under my leadership, parties and organizations which professed hostility to the Government were allowed to hold their incessant demonstrations and protest rallies, supported by their own newspapers and armed groups.

People were arrested while I was in power only for specific crimes and violence, not for their political views or for propaganda purposes. My Government insisted at all times upon the rights of the national minorities in Georgia being considered equal to those of the Georgian population. As for the abolition of South Ossetia's so-called autonomy, this was brought about by the Parliament of South Ossetia itself, which proclaimed the establishment of an independent Republic; and the relevant decree promulgated by the Georgian Parliament merely recognized this fact. The violence and disorder which followed in South Ossetia was provoked by extremist forces directed from Moscow. The political slogan 'Georgia for the Georgians' was never proclaimed by me at all: it was a cynical invention of Moscow's propaganda machine.

Referendum on independence and Presidential elections

A referendum on Georgian independence was held on 31st March 1991, at which more than 90% of the population voted for political secession and independence. Following this result, the Georgian Supreme Council in Tbilisi proclaimed Georgia's independence on 9th April 1991. On 26th May, Georgia held its first presidential elections, and I was elected Georgia's first President.

Shortly after my election, a total political and economic blockade on Georgia was enforced, while every conceivable destructive measure was taken against the legally elected Georgian Government. Despite our Declaration of Independence, Gorbachev invited me to Novo-Ogarevo to sign the Union Treaty. It was following my explicit refusal to do so, that the Kremlin elaborated a concrete plan to overthrow Georgia's constitutional Government.

President Bush contributed personally to this persecution of Georgia when he visited the Soviet Union in the summer of 1991 and persuaded Ukraine to stay within the USSR - denouncing me as a 'man who has been swimming against the tide'. Subsequently, his Secretary of State, James Baker, announced the existence of an authoritarian regime in Georgia that would never receive any assistance from the US Administration. This statement was the signal for the armed 'opposition' to begin its lethal activity. As a Member of the Parliament, Mr. J. Afanasieff, has recently stated, Gorbachev and Shevardnadze diverted 65 million pre-hyper-inflation rubles for the purpose of financing the coup d'etat in Georgia.

Putch

Certain members of the legally elected Georgian Government, and also of the Parliament, who maintained dose contact with Shevardnadze in Moscow, took part in this conspiracy against the Georgian authorities. I refer in particular to the Prime Minister, T. Sigua, and to the Chief of the National Guard, T. Kitovani; the Minister of Foreign Affairs, G. Khostaria; the Speaker of the Parliament, A. Asiatiani; and V. Adamia, N. Natadse, and T. Paatashvili, Members of Parliament, together with others.

Sigua and Kitovani led an agitation campaign within the national guard, which had in fact been set up under my direction, seeking to persuade its members that I had supported the 'August coup' in Moscow. One of the methods they used was to state that I had supported Yanayev [Janaev], and to promise to show members of the National Guard some documents to prove it, resulting from the interrogation of Yanayev. None of these documents have been forthcoming to this day.

The charge was ludicrous because in fact I was the first President to appeal to Western countries on the second day of the Moscow 'coup' (20th August), to recognize that all elected presidents and parliaments in the region must be supported. I added that the organizers of the putsch represented 'reactionary forces'. My appeal was published in the Russian-language Tbilisi newspaper 'Swobodnaya Grusia', and was transmitted to news agencies world-wide.

Another technique used to win over the support of the National Guard was to persuade young, in-experienced recruits that I was planning to dismantle and disarm the National Guard (despite the fact that I had caused it to be established), basing this lie upon a decree I had issued, in which I had laid down that the National Guard was subordinate to the Interior Ministry of which it formed a part, and that this arrangement was necessary in order to protect the National Guard from Moscow's machinations.

By such unworthy means, the Moscow- directed plotters succeeded in enticing onto their side a significant proportion of the National Guard - establishing a new military camp on the outskirts of Tbilisi. This camp was hostile to me personally and to the Parliament, and became a base for disparate members of the so-called 'opposition', including specially released criminals, drug addicts and black marketers. These groups received financing from Moscow and the local Mafia. The Transcaucasian Military District of the Soviet Army (ZAKWO) supplied these formations with arms and armored vehicles, communications equipment, and military instructors.

The Moscow-directed 'opposition' to Georgia's legitimate Government, the Parliament and my Presidency, also received strong support from the Communist intelligentsia, which had enjoyed exceptional privileges under Soviet Communism, and the members of which had lost those privileges following the democratic revolution in Georgia, and were dreaming about a return to the years of rule by Shevardnadze.

Among the most shameless lies put about by the Moscow propagandists at that time was an accusation that I was seeking to isolate Georgia along Albanian lines - whereas of course the truth of the matter was that the authorities in Moscow had isolated Georgia through their own deliberate actions, slandering Georgia as a 'fascist state' groaning under 'totalitarian rule'. The upheavals and disorders in the country were so grave that I had been prevented from traveling to Western countries.

For instance, I had been unable to fulfill my plans to travel to Davos, Switzerland, in January, to visit Denmark in September in response to an invitation from the Danish Parliament, or to address the American Congress in response to its invitation. My inability to take up these invitations was falsely presented to the world as confirmation of my isolationist intentions, and thus proof of my 'anti-European' and 'anti-American' policies.

With effect from September, this coalition of officials who had defected, criminal and Mafia elements, and the so-called 'street opposition', were sufficiently organized to be able to intensify their campaign against the Government - demanding the resignation of the President, the creation of a new 'coalition government', and fresh parliamentary elections. On several occasions, these elements attacked the Parliament building, causing bloody incidents and disorder. They occupied the national television building and attacked the central electricity generating station in Tbilisi. I addressed the armed opposition on several occasions, calling for political dialogue - but without any result.

Cup

Following the collapse of Gorbachev's Novo-Ogarevo process, and recognizing the inevitability of the Soviet Union's disintegration, the Soviet leadership decided to create a new Empire model, the so-called C.I.S., which was to be established at a meeting planned for 21st December 1991 in Alma-Ata, when the leaders of the Soviet Republics were to sign an agreement establishing the new political entity. My refusal to attend this meeting was the development which triggered Moscow's decision to overthrow Georgia's legally elected Government. And no time was lost.

On that very day, 21st December, when the attention of the world was focused on the meeting in Alma-Ata, rallies began outside Tbilisi's Parliament building. One rally was attended by supporters of the legal Government, and another consisted of the armed so-called 'opposition', infiltrated by officers of the Russian Army. Armored cars and military vehicles appeared on the streets. The anti-government forces began to shoot at unarmed supporters of my Presidency, and several people were killed.

Thus the 'opposition' had embarked upon the final phase of its agitation to overthrow 'dictatorship' and to establish 'democracy' by violence, in accordance with the well-known prescription of Lenin. By means of this deceptive plan, supported by Moscow and the Soviet military, a group of putschists, led by the former Soviet Foreign Minister, KGB-General Shevardnadze, set out to overthrow Georgia's legal government, and to usurp power in Tbilisi. I openly and repeatedly warned the Georgian people and the world's governments about this dangerous intention, but unfortunately my warnings went unheeded.

On the following day, 22nd December 199l, the so-called 'opposition' occupied the Hotel 'Tbi1isi' and the Kashweti church in front of the Parliament building, and started shooting and bombing Parliament using artillery, missiles and snipers on the roofs of nearby buildings. The Parliament building was defended by elements of the National Guard who had not been deceived by Shevardnadze and his associates, and remained loyal to the President, but who lacked artillery, missiles, or heavy armour. In the course of their attack on the Parliament complex, the putschists burned down and destroyed all the surrounding buildings - including the Art Gallery, the Painting School, the City's leading college (formerly the aristocrats' gymnasium), and other establishments.

The City's central Rustaveli Avenue was reduced to ruins. My own house, where my wife and two children lived, was surrounded and bombed. Attempts were made to seize my family as hostages, but they were saved by members of the National Guard, by now called the President's Guard, and conveyed by armored car to the Parliament building. After they left, my house was stripped bare by criminal elements, no doubt with 'opposition' consent, and burned to the ground.

The siege of Tbilisi's Parliament building which continued for 16 days, was noteworthy for inhumanity and barbarism. Snipers shot anyone approaching the building, including the vehicles of First Aid workers, and fire engines which were therefore unable to quench the fires. Many houses were razed to the ground, and hundreds of people were left homeless. People who had been defending the Parliament building were killed in cold blood in Tbilisi's hospitals by members of the 'opposition', these putschists fighting for 'democracy'.

At the end of December, the Russian Armed Forces reinforced the armed 'opposition'. After the Presidential Guard had managed to burn several armored vehicles and tanks operated by the 'opposition', new vehicles suddenly appeared. Their main base, the Institute of Marxism-Leninism, was heavily re-supplied by lorries, loaded with arms and ammunition. The accuracy with which shells, mortars and missiles were used was so great, that there can be no doubt that Soviet military specialists participated with the 'opposition' putschists. Moreover, drivers and troops from the Soviet Army were found dead in some of the armored vehicles which the Parliament's defenders had managed to hit.

On 27th December 1991, members of the Presidential Guard who were defending the television station under the command of B. Kutateladse, betrayed the President and yielded the television tower to the 'opposition'. On 2nd January 1992, these forces formed a 'Military council' and a 'Provisional Government', consisting of T. Sigua, T. Kitovani and D. Ioseliani - who was freed from jail for the purpose and linked up with the putchists and his former criminal associates. In parallel with these developments and Ioseliani's release, about 4,000 convicted criminals were also released from the prisons, given arms, and instructed to join the 'army of fighters for democracy'.

Exile

Recognizing that this war against the putschists, blatantly supported by the Soviet military, could not fail to result in further bloodshed, and might end up totally destroying our capital city, I and a group of my armed supporters left the Parliament building on 6th January 1992 under a hail of bullets. We traveled first to Azerbaijan, then on to Armenia, and finally to the Chechen Republic, where the President, Dshohar Dudaev, gave us temporary shelter. From Grozny, the capital of the Chechen Republic, I disseminated the following appeal to the United Nations and to all peoples and governments of the world:

Appeal to the peoples and the

governments of the World.

To all peoples of goodwill.

To the United Nations

'I, popularly elected president of the Republic of Georgia, Zviad Gamsakhurdia, address all the people who value the ideals of democracy, human rights and freedoms and are not indifferent to the fate of the whole nation, which became a victim of a major disaster.

In Georgia in January 1992, the military junta of political adventurers and the local Mafia carried out a coup d'etat in Tbilisi, having forcibly usurped power and started a war against the constitutionally elected government and the President, which led to the deaths of hundreds of people. The capital Tbilisi was partially burned down and historic monuments were destroyed on the main avenue of the city.

In order to put an end to bloodshed, I, the President of the Republic of Georgia, left Tbilisi together with the members of my family, who also were under the threat of physical extermination. The putschists burned down the Parliament building, looted my house, which at the same time is a memorial estate of my father - the well-known Georgian writer Konstantine Gamsakhurdia.

The junta formed a self-appointed government and is committing unspeakable crimes against the people who put up resistance to lawlessness and tyranny. They systematically shoot at peaceful rallies, arresting innocent people including MPs. Their armed forces rob and terrorize citizens. The people have launched a campaign of civil disobedience. Strikes are being carried out at the enterprises, railways and ports. The country's energy and food crisis has reached alarming proportions.

I appeal to the United Nations, to the peoples and governments of the whole world, to issue a denunciation of the gross violations of human rights [committed] in Georgia by the junta, to demand the restoration of the constitutionally elected government and also to offer the Georgian people all the help they need to recover from this disaster, caused by the adventurous actions of the military junta'.

President of the republic of Georgia,

Zviad Gamsakhurdia,

Georgia, 27th january 1992.

Regime

But regrettably, bloodshed continued in Tbilisi and all over Georgia. After seizing power on 6th January 1992, the junta embarked upon systematic repression and a reign of terror, executing supporters of the legally chosen President, killing several hundred of them in Tbilisi alone, and in the countryside to the west of the capital. Near the village of Ninotsminda (Agaiani), murderous gangs were permitted to rob and kill people engaged in peaceful protests in support of my Government. In Tbilisi, hundreds of thousands of people demonstrated, protesting against the banning of the legally elected President and Parliament; and similar scenes were repeated in other towns throughout the country. During these manifestations, about a hundred of my supporters were assassinated, and many hundreds were wounded and detained.

It was always clear that the bulk of the forces of the armed so-called 'opposition' consisted of criminal elements - a fact which was even admitted by the junta's self-appointed so-called Prosecutor General, Vakhtang Rasmadse. His admission appeared later in the newspaper 'Sakartvelos Respublika' dated 25th February 1992.

Thus the notorious gangster Dzhaba Ioseliani, who had been convicted on several counts of murder, robbery and for other crimes, was suddenly elevated to membership of the new self-appointed 'government'. Tengiz Kitovani, another member of the junta, has several past convictions for various offenses committed under Communism. Ioseliani openly authorized, on television, all the atrocities being committed by his controlled gangs of thugs, and threatened all attending demonstrations and protest meetings with shooting and other forms of execution. The influence of this criminal junta on young people is deeply corrupting, given its repulsive use of money, drugs and weapons as enticements.

By day, the junta attacks peaceful protest demonstrations, and by night it terrorizes and robs the population. It imposed a State of Emergency and curfews in Tbilisi and in Georgia's five other main cities, in violation of Article 4 of the Georgian Constitution, which lays down that only the legitimately elected Government and Parliament have the right to announce a State of Emergency.

Later on the illegal junta and its forces commenced punitive operations in various cities and towns, where the protest movement against the overthrow of the legal Government has continued. Many reports, published in unofficial Georgian newspapers such as 'Kartuli Azri', 'Agdgoma' and 'Sakartvelos tsis kvesh', have described acts of ruthless terror and barbarian behavior committed by the illegal junta's forces.

In Easter Georgia, demonstrations and protests took place in Gurdshaani, Telavi, Akhmeta and Kareli. However, after punitive operations conducted by the junta's forces, these demonstrations ceased. By contrast, in western Georgia, where the junta was able to deploy fewer forces, active resistance has continued to this day.

The junta's version of events is that because I am a west Georgian, the people in that part of the country support me more than they do elsewhere. In reality, the electorate in both western and eastern Georgia cast their votes for me in equal proportions; and I received particularly strong support from Georgians in Sagaredsho ('South Ossetia'), Kartli, Kakheti, Meskheti, etc.

The actual reason for the imbalance in the protest movement is the imperfect distribution of the junta's forces of repression, which are mainly concentrated in Tbilisi, Sagaredsho and in other regions of Kakheti, which they are able to control the most effectively. But the junta has launched several punitive expeditions into west Georgia, against the 'disobedient' populations in the towns of Zugdidi, Tsalendzhikha, Senaki, Martvili, and Khobi. Intelligence concerning the resulting brutalities, vandalism, terror, robbery and violence, and about the hundreds of victims among the peaceful populations in those locations, was published in the news- paper 'Sakartvelos tsis kvesh' (which means 'Under the Sky of Georgia'), issue number 37, dated 16th August 1992, printed in the Chechen Republic.

In February 1992, the former US Secretary of State, Mr. James A Baker, visited Moscow and met Shevardnadze and the head of the so-called 'Provisional Government' of Georgia, T. Sigua. The unofficial meetings and negotiations which then took place prepared the ground for the return of Shevardnadze, the former hated Communist dictator of Georgia, to Tbilisi for the stated purpose of guaranteeing 'political and economic stabilization, peace and democratic elections'. During his visit to Tbilisi, I sent a telegram of protest to Secretary of State Baker in the following terms:

'I express my protest against your intention to visit Georgia, which means support of the most illegal, anti-democratic, criminal and terrorist regime in the world, which has overthrown the legal authorities [who were] elected by the people, which wages war against its own people, rudely violates human rights and fundamental freedoms, chastening and shooting at peaceful meetings and demonstrations, has imposed a monopoly over the entire mass media, and collaborates with and stimulates the activities of, the underworld and the Mafia.

In seven towns and cities of Georgia including Tbilisi, there is still a curfew. Real power is in the hands of the notorious criminal and gangster Ioseliani. The criminal junta misappropriates all humanitarian aid received from the West and resells it on the black market at sky-high prices, while the people receive nothing. The economic situation is catastrophic; hunger, chaos and total destabilization are increasing; there is a great lack of foodstuffs and medicines; many people are dying of hunger and various diseases every day, especially old people and children.

Shevardnadze is reviving Stalinism in Georgia, has begun mass repressions and tortures; innocent citizens are arrested every day in large numbers because of their part in organizing protest actions; meetings, demonstrations, hunger strikes, strikes and protests are prohibited; and there is strict censorship throughout the country.

In such a situation, all possibility of free and honest elections is excluded. The situation [prevailing] in Georgia will soon come to resemble that in Somalia and Ethiopia. The United States' Government's actions in supporting this criminal totalitarian regime and establishing diplomatic relations with it, amount to a rude violation of all the democratic principles upon which American society is based, a violation of the [principles of the Helsinki Final Act, of the Charter of Paris, and of international law - a state of affairs which has induced indignation among the Georgian people, which is aware of the United States' positions vis-?is Cuba, Venezuela and Haiti.

As a result [of the position adopted by the United States], anti-American feelings are increasing. I demand from the US Administration that it should cease its [open] support of state terrorism in Georgia, and that it should establish contacts only with the legal authorities of Georgia, who are now in exile'.

Nomenklatura

It was not long before Shevardnadze himself arrived at Tbilisi airport, where he was met by a group of 'Mkhedrioni' gangsters, militiamen and some Nomenklatura intellectuals - his supporters. He saluted these intellectuals from the Nomenklatura, "who had taken up arms and fought for the establishment of 'democracy'". Then he went first to the Sioni church, simulating piety, where he was welcomed by the local 'Patriarch', a long-term agent of the KGB, before proceeding to 'Government House', where he was there and then 'elected' as head of the new anti-constitutional body - the so-called 'State Council', which was in fact the same as the Military Council, but broadened and disguised.

Following his arrival on the scene, Shevardnadze presided over increased mass repression and a heightened reign of terror against his innumerable political opponents, who had continued to hold meetings and demonstrations, now against his arrival and his blatant usurpation of power. Punitive operations were carried out and repeated several times in western Georgia, with greater brutality and ruthlessness than before. Meanwhile the scale of assistance to the junta and its terrorist formations provided by the Russian military was stepped up, with supplies of armaments, technological equipment for warfare, and specialists.

Soon after Shevardnadze's arrival in Tbilisi, his gangs again attacked, robbed and burned my home at 19, Gali Street, which also served, as I have mentioned, as a memorial and museum to the memory of my father, the well-known writer Konstantine Gamsakhurdia. My house remains a burnt-out ruin to this day, in exactly the same condition as after these attacks, in spite of public remarks by Shevardnadze about his 'friendship' with Konstantine Gamsakhurdia. To make matters even worse, my house has been repeatedly defiled by members of the junta's mobs.

The West

Western politicians, and most of the mass media in the West, kept silent about the reign of terror, the repression and the barbarian vandalism unleashed in Georgia following the illegal seizure of power by the junta. The exceptions were the press in Finland and newspapers in Switzerland, which described the truth about the newly installed terror regime and the crimes it was committing. The United Nations, the CSCE, the Red Cross and most human rights organizations refused to investigate the facts about state terrorism and the human rights violations being suffered by the Georgian people - the exceptions here being IGFM, the International Society of Human Rights (based in Frankfurt), and the Finnish Helsinki Group. Both of these organizations manifested deep concern about these tragic events in Georgia.

Western cynicism and hypocrisy reached unheard-of levels with the further visit paid by Mr. James Baker to Georgia, on the anniversary of our independence, 26th May 1992. While Mr. Baker congratulated Shevardnadze and his boorish supporters gathered in the Square of the Republic in front of the Hotel 'Iveria', and spoke about democracy, about 200 meters from where Mr. Baker was speaking, a large force of 'Mkhedrioni' chastisers and police with dogs were busily engaged in dispersing another meeting of my supporters, shooting at the crowd, and beating people without mercy. Baker overheard this shooting in the streets, but made no comment, carrying on with his speech.

The CSCE's biannual summit meeting took place in Helsinki in early July. As the President of Georgia, and founder of the first Helsinki Group in 1975, I was invited to attend by the Georgia group in the Finnish Parliament. Mr. Heikki Riihijavi, the leader of that group, made three unsuccessful applications to the Finnish Ministry of Foreign Affairs in an attempt to obtain a visa for me to attend the CSCE Summit. The Ministry informed Mr. Riihijavi and the Chairman of the Finland-Georgia Society, Mrs. Aila Niinimaa-Keppo, that I would only be allowed to arrive in Finland after the conclusion of the Helsinki Summit. No explanation was given to the Finnish Parliamentary Group concerning this delay to my visit; and nor was any explanation forthcoming about the fact that members of the 'Mkhedrioni' gangster formations and officers from the KGB were allowed to enter Finland, whereas I was not.

Faced with this situation, Mr. Riihijavi complained, with justification [see ABN Correspondence, May-June 1992, Number 3, Volume XLIII]:

'This goes against the rules of the CSCE, which is based upon respect for legality, democracy and access to information and freedom to travel within the territories of the CSCE member states. How can the CSCE stop Gamsakhurdia from coming to Finland, while heartily welcoming Shevardnadze, who was involved in last year's putch and who masterminded the illegal takeover in Georgia? The CSCE was meant to protect nations against criminal leaders like Shevardnadze'.

I sent a similar letter of protest directly to the CSCE, but without any result. Meanwhile, Shevardnadze had taken part in the Helsinki Summit as a messenger of peace and democracy. By this illegal behavior, the CSCE violated its very own document, drawn up at the Moscow meeting of the participating states at their meeting lasting between 10th September and 4th October 1991. Specifically, the CSCE violated Article 17.2 of that document, which declares:

'If in any participating state an attempt is made to overthrow, or the overthrow takes place of, the democratically elected government by undemocratic methods, the participating states will support the legal bodies of the state concerned, in accordance with the United Nations Charter'.

In Georgia's case, this solemn stipulation was reversed. After receiving the blessing and approval of the CSCE - amounting, as one Finnish newspaper put it, to 'a license to kill' - Shevardnadze's bloody regime redoubled the intensity of its reign of terror all over Georgia. It did so, too, in the knowledge that it had the tacit support of the United Nations, as well as of the CSCE. Faced with this further onslaught, people in western Georgia have organized themselves to conduct guerrilla warfare against the marauding gangs and formations dispatched by the junta, which have been invading towns and villages. Many partisans have been tortured and executed by Shevardnadze's junta.

As reported by SOVIET ANALYST, on 24th June 1992, Shevardnadze's secret services feigned a 'coup attempt', when some of my unarmed supporters were lured into the TV building by officers from the Ministry of Interior's troops, with the promise of an opportunity to broadcast their appeals to the Georgian people, without charge. When they accepted this offer, they were arrested and tortured. Shevardnadze's junta announced that an 'unsuccessful coup d'etat had taken place; and to dramatize the situation, provocateurs under the control of Ioseliani carried out terrorist atrocities, in the course of which several people were killed. The provocateurs then 'confessed' on television that they had received instructions from myself to commit these acts of terrorism. In response to this episode, I sent a telegram to Shevardnadze, in which I accused him of trying to discredit me using the methods of Stalin and Beriya.

War in Abkhazia

Turning now to Shevardnadze's policy concerning national minorities. In his propaganda, Shevardnadze accused me of being a 'fascist', a 'nationalist' and an 'enemy of the national minorities'. Now, however, he is visiting upon them direct violence and genocide - depriving them not merely of their autonomy, but also of even the right to live and exist. On 11th August 1992, troops of the 'State Council' embarked upon an extensive punitive campaign in the Abkhazian Autonomous Republic. Shevardnadze and his 'State Council' insisted that this invasion was necessary for the purpose of sustaining public order in this region, especially along railway lines. But the fact is that, following this invasion, the region has experienced, and continues to suffer, wholesale public disorder, anarchy, genocide, and total destruction and burning of entire towns and villages. In reality, Shevardnadze's objective was to overthrow the authorities in the Autonomous Republic.

What irritated Shevardnadze was that the authorities of this Autonomous Republic had not been persecuting my supporters, and had refused to introduce totalitarian rule, as practiced by the junta, in Abkhazia. There had been no reign of terror or repression of my supporters in Abkhazia, where the people had continued to enjoy political freedom, were able to publish their own newspaper 'Agdgoma', and were free to speak out on local television.

It is evident that the main purpose of the Abkhazian war is to establish in this region Shevardnadze's dictatorship and the rule of his junta and Mafia. The war in Abkhazia, which had already cost 4,000 lives by the end of last year, seems to be without end [culminating recently in the virtual flattening of Sukhumi: -Ed.]. The most descriptive expression to date of the true objectives of this war of oppression in Abkhazia, and of Shevardnadze's approach to the question of solving the problems of the minorities, came from Shevardnadze's Commander-in-Chief, 'general' G. Karkarashvili, who explained on a national television programme [25th August 1992]:

'If Abkhazia does not cease its resistance, my troops will kill all 97,000 Abkhazians'.

In other words, Shevardnadze and his murderers are prepared to liquidate the entire nation [- a process which appears to be well advanced: - Ed.]. For this purpose, too, Shevardnadze and Karkarashvili are evidently prepared to sacrifice approximately 100,000 Georgians, as well.

This, then, is the nature of the policies of Shevardnadze - former Communist dictator of Georgia, KGB General, promoter of terror, robbery, rape and genocide of national minorities and of his political opponents.

On 29th October 1992, the Defense minister, Kitovani, stated on Moscow Television that that autonomous regions are to be liquidated in Georgia, and that the matter of the autonomous regions will be resolved by military force. This statement, alone, makes it abundantly clear that, despite 'democratic elections' [see below] in Georgia, the country remains a terror dictatorship ruled by a criminal junta - and that all talk by Shevardnadze about 'civilian rule' prevailing in Georgia are lies. Furthermore, by involving the north Caucasian peoples in his Abkhazian war, Shevardnadze and his junta are preparing the ground for a new Yugoslavia in the Caucasus. Western Georgia, including Abkhazia, is simply in ruins, with thousands of refugees fleeing these regions daily.

False elections

Concerning the elections, which Shevardnadze promised to hold in Georgia 'in accordance with all the standards adopted in democratic countries', I would like to ask the democratic world whether, in any democratic country of the West, the following behavior is normal:

'Elections' are 'called', not by an elected body, president, or parliament, but by some illegal, self-proclaimed gathering called a 'State Council' which possesses no legitimacy and imposed itself upon the country by force.

The 'election' organizers fail to identify the electors by name and address, omitting to carry out the preparations necessary to ensure absolutely fair voting.

The people are subjected to intensified terror and repression ahead of the 'election', and are forced in many cases to provide written undertakings that they will vote for a single candidate for the post of Speaker of Parliament - the top post in Georgia.

The position of Speaker of Parliament is decided not by the votes of MPs, but in fact by 'public voting'.

'Elections' take place against a background of civil war, anarchy, and curfews in many towns and cities.

'Elections' take place without secret voting in most districts.

However, in a few districts of the capital, electoral arrangements, ballot boxes and booths for 'secret voting' are rigged up for the benefit of intentional observers, who are misled into deducing that the ballot boxes and booths for secret voting are replicated throughout the city and the country.

Moreover, the international observers are steered away from all other polling stations (where the voting arrangements are decidedly not secret).

At most polling stations, the 'elections' are conducted under the control of gunmen, who watch the voters as they place their votes, and check for whom they have voted. If they have not voted in accordance with the gunmen's 'preferences'.

... the gunmen visit such 'disobedient' voters with ballot boxes, and force them under threat of death to 'amend' their previous vote, and to place their vote in accordance with the 'party line'.

Armored vehicles pursue 'electors' in the streets and drive them to the polling stations by force - a practice observed in the west Georgian town of Martvili.

Noticing that the number of ballot- papers cast is hopelessly insufficient for the authorities' purposes, the 'Election Commission' removes the boxes and replaces them with new ones - an activity observed, for instance, in the town of Vani.

People are seen stuffing ballot-boxes with 100-200 ballot papers.

Local 'Election Commissions' consist of carefully selected people loyal to the illegal government, without any involvement by the opposition.

So-called 'democratic elections' take place without any involvement on the part of opposition parties or individuals.

Was it not quite natural that, following such 'elections', the dictator Shevardnadze was 'elected' by 96% of the 'electorate'? Elections like these were of course standard under the Communists; and it is no coincidence that Communism has been revived in Georgia under Shevardnadze with great success, incorporating many of the 'innovations' introduced when Shevardnadze was in power earlier.

Shevardnadze has since boasted that he presides over a 'democratically elected' parliament in Georgia. It is curious, therefore, that 15 days after the elections, only a proportion of the parliamentary lists had been published - although even among the names published to date, the distribution of forces was remarkably favorable to Shevardnadze. Among these names were very well- known nomenklatura-plutocrats, including notorious accomplices of the events of 9th April 1989, and Mafia bosses - all of whom had unaccountably emerged with huge majorities in the new 'parliament'.

The rest of the new parliamentary lists were published after a long delay, due to the fact that there erupted a great struggle among 'candidates' for inclusion within the favored Nomenklatura 'parliament', and a burning desire among their number for the opportunity of proving by their words (and deeds) their undying fidelity to the 'Speaker'.

But all of a sudden, Shevardnadze announced, on 21st October 1992, that the first session of the new 'parliament' had been delayed for an indeterminate period, due to the 'complicated situation' prevailing in Georgia. In actual fact, the real reason for this delay was a political struggle between the 'deputies' and a growing, indeed acute, danger from Kitovani, who threatened a fresh putsch, should he be removed from the position of power he had usurped.

As for Shevardnadze's boasts about the introduction of the market economy and the country's prosperity, the economic situation in Georgia is in fact catastrophic. The Russian Federation has allotted Georgia credits in the sum of 20 billion rubles [source: the Moscow-based newspaper 'Kuranti', October 1992, No. 38 [59]], while the United States and Turkey have assisted Georgia with several million dollars. All these credits,, as well as the humanitarian aid, are being systematically misappropriated by officials - applied for personal profit and for the financing of the Abkhazian war and punitive expeditions in west Georgia (Megrelia).

Privatization in favor of the Nomenklatura, is implemented on the orders of the junta members Ioseliani and Kitovani, and by others - with all national property and sources of valuable production distributed among the Nomenklatura/Mafia bosses.

Not surprisingly, most of the Georgian population, especially in the towns and cities, is on the verge of abject poverty and starvation. The agricultural sector has been totally paralyzed, especially in western Georgia. The main reasons for this breakdown are the civil war, a lack of fuel, an absence of agricultural equipment and technology, and the absolute chaos which has accompanied the privatization in favor of the Nomenklatura (known as 'Nomenklatura-privatization) of the land, which has been taking place without any legislative basis, in the absence of any law governing land and property, and in the midst of endless conflicts among landowners as they struggle against the former state farms for property, and production, while having to contend with banditry and robbery, and with the wholesale misappropriation of assets.

Even the illegal government's media has admitted that in Tbilisi alone between three and five men die of hunger every day - a figure dismissed by our sources as a gross understatement of the position, which is that dozens are dying every day from lack of food to eat.

Conclusions

In conclusion, I need to add that Shevardnadze's criminal regime is in the habit of repeatedly violating the Charter of the United Nations, the Declaration of Human rights, all principles of intentional law including the Helsinki agreement and the Paris Charter, and all declarations, pacts and conventions on Human rights and fundamental freedoms.

The regime operates by means of ruthless terror and violence, which are the main principles and instruments of state policy in Georgia.

It has no right to represent Georgia at the United Nations and in the forum of the CSCE, and it must be thrown out of these organizations. This heinous regime, which has brought Georgia to a state of political and economic catastrophe, is in the process of creating great dangers of destabilization and warfare throughout the Caucasus region, with the possibility of the war spreading even into Russia, and further fueling the basis for the emerging world crisis.

I, the legally and democratically elected President of Georgia-in-Exile, therefore appeal to the United Nations, to the governments and parliaments of the world, to the mass media, to all international political and religious organizations, and to all men and women of goodwill, to help Georgia in the midst of its terrible disaster, to condemn the state terrorism practiced by Shevardnadze's regime, to impose a total boycott on it, and to help restore the legal Parliament and Government.

Unless this happens, there can be no peace, stabilization or democratic development in Georgia, and throughout the whole of the region of the Caucasus.

The modern Abkhazian ASSR lies in the north-western region of Georgia – in the historical and modern Western Georgia.

There is no consensus in the scholarly literature regarding the oldest ethnic map of Western Georgia, particularly its Black Sea littoral. However, this refers to such a remote period (6th-5th millennia B.C.) about which there cannot be any discussion of a concrete ethnos, whereas from the 2nd millennium B.C., when the picture is relatively clearer, mainly Kartvelian population is assumed in Western Transcaucasia.

Beginning with the indicated period up to Classical times, the archaeological material permits to conclude the existence here of a common Colchian, i.e. Kartvelian culture. According to specialists, separate regional-local variants are identifiable within this major culture, yet Colchian on the whole. In the 2nd and 1st millennia B.C. the Kartvelian (properly Svan) ethnic element was widespread in the mountainous as well as lowland zone of Western Georgia, one proof of this being the derivation of the name of Tskhumi (Sukhumi) from the Kartvelian (Svan) designation of hornbeam.

The conclusion is supported by the evidence of ancient Greek mythology – the expedition of the Argonauts to Colchis, and by the view-based on linguistic research – on the existence here of a Kartvelian language by the time of the advent of the Argonauts (2nd millennium B.C.), i.e. at the time of earliest contacts between Greeks and Colchians.

Such a view is fully backed by evidence of Classical written sources (Hecataeus of Miletus, 6th cent. B.C., Herodotus, 5th cent. B.C., Scylax of Caryanda, 4th cent. B.C., Strabo, turn of the old and new eras, and others), on the basis of which we find the statement in the specialist literature to the effect that at the period under discussion the Kingdom of Colchis embraced the entire lowland of Western Georgia. The land up to Dioscurias (Sukhumi) appears to have been populated mainly by Colchians, beyond which the population was relatively more mixed, with the Cercetae, the Coraxae, and other tribes being mentioned along side the Colchians. Some researchers consider these tribes of North-Caucasian origin. However, note should be taken of the fact that Hecataeus of Miletus calls the Coraxae 'a Colchian tribe'. In defining the ancient ethnic map of Georgia, significance attaches to the fact also that Arrian and Claudius Ptolemaeous, authors of the 2nd cent. A.D., refer to the geographical point 'Lazica' close to Nikopsia (modern Tuapse). It should be borne in mind that Arrian calls the place 'old Lazica', this being an authentic proof of the existence here of Colchian-Laz population.

It is absolutely clear from the evidence of Classical sources that in the 6th-1st cent. B.C. the territory of the modern Abkhazian ASSR was entirely within the Kingdom of Colchis. From Apsarus to Dioscurias (Sukhumi), the territory was inhabited by Colchians proper, then began a relatively mixed region where, alongside Colchians there lived other tribes as well (Kartvelian and perhaps non-Kartvelian too). To the north of the Colchians, the mountains were settled by the Svans; the habitat of the latter appears to have extended to Dioscurias. In this respect, considerable interest attaches to Strabo's evidence on the Savan over-lordship of Dioscurias.

From the 1st-2nd cent. A.D. the Apsilae and the Abasgoi are mentioned on the Black Sea littoral of Western Georgia. There is a difference of opinion as to the time from when the Abasgoi and the Apsilae, mentioned as inhabiting the Black Sea littoral in the 1st-2nd cent. A. D., lived here. In the view of some researchers, they had inhabited the region from earliest times but, since they belonged to the Colchian historical, ethnic and cultural word, they failed to be reflected in early sources. Other researchers believe that they appeared here with the mass settlement of Abkhazian-Adyghe tribes from the Northern Caucasus. There is also a difference of opinion concerning the ethnic affinity of these Apsilae-Abasgoi. Some researchers consider them to have been North-Caucasian Adyghe tribes. It has also been suggested that they are the same Kartvelian tribes as their neighbouring Egris (Laz), Svans, and others, while the modern Abkhazians are the Apsua that immigrated from the Northern Caucasus from the 17th century. Some scholars adhere to the autochthony-cum-migration view. i.e. the tribes under discussion are partly indigenous and partly immigrant It has been hypothesized that the 'Abeshia', mentioned as the general name of the north-eastern Asia Minor mountaineers in 11th century B.C. Assyrian inscriptions may – due to the resemblance of the name – have been the ancestors of the Apsilae mentioned in Classical sources as inhabitants of the Black Sea littoral, later moving from the south to the north.

The Apshileti of Georgian medieval sources (Juansher) corresponds to the Apsilia of Greek sources. Juansher mentions Apshileti in connection with the expedition of Murvan ibn Muhamad against Western Georgia in the 730s.

Apshileti and its Prince Marin are mentioned by Theophanes the Chronographer in connection with the developments of the early 8th century. Henceforward there is no reference to Apshileti in the sources, which is accounted for by the fact that Apshileti ceased to exist as a political entity and, becoming part of Abkhazia, it came to be known under the name 'Abkhazia' ('Abazgia').

This was the first step of the broadening of the concept of 'Abkhazia' and this process occurred gradually.

Following the disintegration of the Kingdom of Colchis, several principalities, politically dependent on the Roman Empire, came into being. Among these Arrian name the principalities of the Apsilae and the Abasgoi.

In the second half of the 2nd cent. A.D. Western Georgia was united the Kingdom of Egrisi (Lazica). Apshileti proper, from the river Egris-tsqali (Ghalidzga) to the Kodori river, was within the Kingdom of Egrisi, while Apshileti, north of the Kodori, was united to Abkhazia, the latter, being a vassal of the Kingdom of the Laz.

This kingdom of Lazica of the Greek written sources (according to the Georgian sources, the Kingdom of Egrisi) was an immediate successor of the Kingdom of Colchis. When narrating about Lazica and the Laz, the 5th century Byzantine anonym and the 6th century historians: Procopius of Caesarea, John Lides, and Agathias Scholasticus note, as a rule, that the Laz are the successors of the ancient Colchians, that they were called Colchians in the past, that the Colchians are the ancestors of the Laz. These historians use the two terms synonymously.

In the 6th century, the Kingdom of Egrisi weakened gradually as the result of the Byzantine-Iranian wars. By the end of the 6th century Abazgia seceded from the Kingdom of Egrisi and became directly subject to the Byzantine Empire, the Abazgian princes (archons) becoming the emperor's vassals. Arab inroads also contributed to the further weakening of Egrisi. Abazgia gradually gained strength, for – as already noted – it now embraced the land of Apsilia (Apshileti) as well. Apsilia (Apshileti) ceased its political existence, and the significance of the concept of Abazgia (Abkhazia) broadened. It seems noteworthy that, in telling about the campaign of the Arab commander Murvan the Deaf in Western Georgia in the 730s, Juansher states that he destroyed the city of Tskhumi of Apshileti and Abkhazia. It is notable that such a reading of the text, namely that Tskhumi was a city of Apshileti and Abkhazia, has been preserved in the oldest extant manuscript (Queen Anne's) of Kartlis Tskhovreba. In the later MSS Apshileti is absent. Apparently, earlier there was awareness of Tskhumi being a city of Apshileti, but m the time of Murvan the Deaf Apshileti was already Abkhazia, politically. Subsequently this knowledge was lost and Apshileti dropped out of the context in the later MSS.

From the 780s, when Abkhazia and Egrisi united and the resulting state embraced the whole of Western Georgia, the meaning of the term Abkhazia' broadened still more; henceforward it designated the entire Western Georgia, and (in written sources) Abkhazians (Abazgians) proper as well as West-Georgians came to be called Abkhazians.

When Western Georgia united in the 780s Leon, Prince of the Abkhazians, became head of the state. The state extended from Nikopsia to the Chorokhi Gorge, and from the Black Sea to the Likhi Ridge, acknowledging Byzantine sovereignty. Ioane Sabanisdze calls the head of that state mtavar ('Prince').

According to Georgian written sources (other sources do not exist), Archil, the last male scion of the (royal) house of the Erismtavars of Kartli, gave the daughter of his deceased brother Mir in marriage to Leon, Prince of the Abkhazians, on whom the crown of Egrisi was conferred. Thus, Leon received Egrisi and the royal crown of the Kingdom of Egrisi through marital links, i.e. by inheritance, which meant symbolic and actual unification of Egrisi and Abkhazia. This gives ground for the view according to which the union of Egrisi and Abkhazia was a dynastic, voluntary act. Later, the same Leon (at the end of the 8th century)r freeing himself from vassalage to Byzantium, declared himself king. According to Matiane Kartlisa, "and held Abkhazia and Egrisi up to Likhi". Abkhazia was Leon's hereditary land; Egrisi was also inherited by him through dynastic marriage. And Leon 'possessed' these two countries equally, bringing them under his power independently of the Empire and "assuming the name of King of the Abkhazians". He assumed the latter title because the dynasty derived from the Principality of Abkhazia. The ethnic affinity of the Leon is unknown, for there is no indication on this in the written sources. Some researchers consider them Abkhazians proper, some believe them to have been Greeks, and some, Georgians. The three views remain within the hypothetical sphere with an equal right of existence. However, this is not essential. Important is the fact that with its language, writing, culture, religion, and policy the Abkhazian Kingdom was a Georgian state, and their kings – judged by these characteristics – were Georgians. It should perhaps be noted here that some 10th-11th cent. Armenian historians, e.g. Ovanes Draskhanakertsi refer to this state (the Kingdom of Abkhazia) as 'Egrisi', and to their king as 'the King of Egrisi', and the inhabitants as 'Egrisians'.

The Kingdom of Abkhazia was a Georgian (Western Georgian) state. A vast majority of its population were Georgians: Karts, Egris, Svans, and part were Abkhazians proper. According to Vakhushti Bagrationi, the Abkhazian Kingdom consisted of eight administrative units or saeristavos (eristavates). The saeristavo of Abkazeti and partly that of Tskhumi were inhabited by Abkhazians proper, while the remaining six were populated by Kartvelians: Egrisi (centre; Bedia), Guria, Racha-Lechkhumi, Svaneti, Argveti (centre: Shorapani), and lowland Imereti (centre: Kutaisi).

It was during the existence of the Abkhazian Kingdom (9th—10th cent.), and with the active participation of Abkhazian kings, that the Kingdom of Abkhazia finally seceded – in Church matters – from Constantinople, becoming subordinated to the Mtskhetan See.

It was difficult to break loose of the political influence of Byzantium, but it was more difficult to eliminate the ecclesiastical dominance of Constantinople. To this end, the Abkhazian kings abolished Greek episcopal sees that served as Byzantine strongholds. Thus were abolished the Poti, Gudava, and other Greek sees. In their place the Abkhazian kings established new Georgian episcopates. Thus, in the time of Giorgi II (922-957), King of the Abkhazians, the Chqondidi See was founded, in the time of Leon III (957-963) the Mokvi See, and in place of the abolished Gudava Episcopate that of Bedia was set up by Bagrat III (975-1014). These episcopates were centres of Georgian culture. Henceforward, the Georgian Church opposed its Greek counterpart with the Georgian language. The Georgian Church built its own churches and monasteries in the Abkhazian Kingdom.

Hagiographic and hymnographic works were written in the Kingdom of Abkhazia. Here, at the Abkhazian royal court was written the Divan of the Kings or the History of the Abkhazian Kings; in Georgian language. The Kingdom of Abkhazia took an active part in the great struggle resulting in the creation of a single Sakartvelo feudal state.

Had the kingdom of the Abkhazians not been a Georgian state its capital would not have been Kutaisi, centre of ancient Georgian statehood and culture, in the heartland of Georgian population, but Anakopia, centre of the Abkhazian saeristavo; its Church would have not seceded from the Patriarchate of Constantinople, and if it did, It would have constituted itself into an Abkhazian proper Church and would have not joined the Catholicosate of Mtskheta, nor would it have introduced Divine Service in Georgian.

From the beginning of the 9th century-if not earlier – the Georgian language gradually acquired a dominant status in the Kingdom of the Abkhazians, becoming the language of culture, the Royal office, and the Church; Georgian epigraphy is evidenced in the Abkhazian Kingdom from the 9th century.

Thus, as already noted, with the establishment of the Abkhazian Kingdom, the meaning of the terms "Abkhazian" and "Abkhazia" broadened, and now it designated Western Georgia, as well as Western Georgian and Abkhazian proper.

The meaning of the term 'Abkhazian' and 'Abkhazia' broadened further from the 10th century, for the title of the kings of the unified Georgia began with that of 'King of the Abkhazians'. Bagrat, the heir-apparent to the Royal House of the Bagrationis ('the king of Kartvelians') was crowned first as 'King of the Abkhazians', for he was the only legitimate successor to the Kingdom of the Abkhazians in his mother's line. He received the title 'Kings of the Kartvelians only at the beginning of the 11th century, on the decease of his ancestor 'King of the Kartvelians. Following the incorporation of Kakheti and Hereti, Bagrat received also the title of 'King of the Hers (Heretians) and the Kakhis (Kakhetians)'. Thus, at this stage the title of the kings of the united medieval Georgia assumed the following form: "King of the Abkhazians, the Kartvelians, the Hers, and the Kakhis".

As a rule, in Georgian written sources of the period under discussion 'Abkhazia' and 'Abkhazian' generally implied (Sakartvelo) and Kartveli).

As 'King of the Abkhazians' came first in the title of the kings of unified Georgia, in foreign sources 'Abkhazian' was used generally in the meaning of Georgian, and 'Abkhazia' as designating Georgia. Incidentally, the foreigners – Greeks, Arabs, Russians – were well aware that 'Abkhazia' was the same 'Iberia' or Georgia. Thus, the Byzantine historian George Cedrenus refers to the Georgian King Giorgi I as the archon of Abkhazia, while his son, King Bagrat IV, as the archon of Iberia. John Zonaras, Byzantine historian of the turn of the 11th and 12th cent., refers to the same Bagrat IV as the Archon of Abazgia. In narrating about the Georgian campaign of the Emperor Basil II, Cedrenus writes that Basil set out against Giorgi the Abazgian, marching towards Iberia. In oriental (Arabic, Persian) sources Abkhazian stands for Georgian, and Abkhazia for Georgia. The 13th century Arab geographer and historian Yaqut writes that Abkhazia was a country inhabited by a Christian people called Kurj. According to Ibn Bibi, Selchuq chronicler of the end of the 13th century, Tamar was the Queen of the Gurj (i.e. Georgians, M.L.); she ruled the Kingdom of the Abkhazians, the capital of which was Tbilisi. Abkhazia was identified with Georgia by Nizami Ganjevi, Khaqani, and others. It should be noted specially that according to Russian medieval sources, Iber is the same Abkhaz (Obez). Many more examples could be cited. The literature on this subject is extensive. There can be only one conclusion: 'Abkhazian' (appearing in various spellings) in medieval Georgian and foreign written sources, as a rule, means a Georgian. Abkhazian proper, which in the 9th–10th century West-Georgian state of the Kingdom of the Abkhazians was represented by the eristavates of Abkhazeti and Tskhumi, in the period of the existence of united Georgia was represented by a single eristavate – that of Tskhumi; its eristavi was Shervashidze.

The maximal extension of the meaning of the term 'Abkhazia' was following by a reverse process.

As is known, at the end of the 15th century, the unified Georgian state disintegrated into four independent states: the Kingdoms of Kartli, Kakheti and Imereti, and the Principality of Samtskhe. Abkhazia was part of the Kingdom of Imereti. The process of the feudal break up of the country deepened with the Principalities of Guria and Samegrelo (Megrelia, Mingrelia) coming into being. Abkhazian was within the Principality of Samegrelo (Odishi), and in the 17th century it (Abkhazia) constituted itself as a separate principality headed by the Shervashidzes. The Abkhazian Principality of the late feudal period was culturally and politically the same 'Georgia' as were the other 'Georgias'. Now, the land to the south-east of the Kodori formed part of Egrisi from the commencement of feudal relations (by tradition from ancient times). This land became part of Abkhazia in the 17th century. After the founding of this (Abkhazian) principality, the Georgians called its inhabitants Abkhazians proper.

From the 15th—16th centuries complex processes were in evidence in Georgia. Nomadic tribes from the Northern Caucasus began to settle in Georgia. This immigration process – timed to the gravest situation obtaining in Georgia – resulted in the settlement of Daghestanian tribes in Kakheti, of Ossetes in Inner Kartli, and of people of Circassian-Adyghe stock in Western Georgia.

At the end of the 15th century, Georgia broke up into four independent Georgian states. From the end of the 15th and the beginning of the 16th cent. Georgia's neighbour in the south-east was the powerful and aggressive Safawi Iran, and on the south-west the powerful and likewise aggressive Ottoman, state. Throughout the 16th-18th centuries there was almost incessant warfare between these two powers (if there was a lull, the sides were preparing for fresh hostilities). This warfare, waged for the spheres of influence in the Near East, had as one of its main aims the subjugation of Georgia, her territory serving as the arena of hostilities. The Georgian states resisted as best they could the encroachments of Iran and Turkey. The struggle took a heavy toll, resulting in a drastic reduction of the Georgian population. The southern slopes of the Caucasus Range, with their population diminished or frequently deserted, were occupied by people crossing from the northern slopes. The migration of the population from the hills to lowland areas is a natural process in mountainous countries, for the barren nature of the mountains fails to provide livelihood and the surplus population descends to the valley. Under peaceful conditions this is a normal process and is kept under control by the authorities. However, when the state is weakened and the process gets out of hand a grave situation arises. It was under such conditions that the socalled free ('lordless') communes of Char-Belakani came into being in Kakheti and in the mountainous region of Inner Kartli; and later in the foothill zone and in the valley too there appeared a compact Osetian population – people migrated from the north and settled on the south-western slopes of the Caucasus Range. We do not know how the people settling here were called in their original homeland. Presumably, Georgians called them Abkhazians' by analogy with the local Abkhazians! From that time, I Christianity began to lose ground in Abkhazia, due, on the one hand, to the bringing by the immigrant population of their pagan beliefs, and on the other, to the ascendancy of the Turks who sought to establish here.

Georgian and foreign written sources give a clear indication of the narrowing of Georgian and Christian positions from the 15th century onward.

The secession of the Principality of Abkhazia from that of Samegrelo was followed by incessant feudal strife. At the end of the 17th century, the Abkhazian princes seized the part of Samegrelo lying between Kodori and the Inguri rivers, annexing it to the Principality of Abkhazia. This is the region known under the name of Samurzaqano. From that time began the 'Abkhazianization' of Samurzaqano. This process of 'Abkhazianization' is well reflected in Georgian – chiefly documentary – and foreign written sources. The process in question is discussed in the specialist literature as well.

After the 15th century, the Abkhazians started raids against various provinces of Western Georgia, mainly Samegrelo. Vakhushti Bagrationi describes nearly all the inroads of the Abkhazians into Guria and Samegrelo in the 17th century and the first quarter of the 18th cent. Foreign written sources also tell about such raids.

Documents of the 15th century clearly distinguished Sukhumi (Tskhumi) from Abkhazia. According to Archangello Lamberti (mid-17th cent.), Dranda, Mokvi, Ilori, and Bedia were in Egrisi.

The 15th cent. Georgian monument "Teaching on the Faith" states that "Abkhazia has totally abandoned Christianity – it has parted from the teachings of Christ". It was these Abkhazians, who had abandoned the teachings of Christ, that made inroads into Abkhazia. A document of the first half of the 17th century ("Levan Dadiani's letters patent granted to the Khobi church on the renewal of the possession of estates") states: "At that time the Abkhazians turned to godlessness and infidelity", "the Abkhazians corrupted the faith and the Catholicosate". The same documentary material shows clearly the gradual narrowing of the jurisdiction of the West-Georgian Bichvinta Catholicasate and the loss of the land for Christianity and the Georgians. According to Lamberti and other foreign authors Dranda, Mokvi, Ilori, and Bedia in the mid-17th century were still within Egrisi; at the turn of the 16th and 17th cent. Nazhaneuli, across the Inguri, was still a Megrelian village. According to the 1626 Great Defter of the Abkhazian Catholicosate, Nazhaneuli was in Egrisi, and a document of 1639 locates the same village in Odishi. The situation changed materially at the beginning of the 18th century. In a document of 1712 the Catholicos Grigol Lortkipanidze wrote: "At Nazhanevi the Abkhazian had driven out the village. The Catholicos Nepsadze had placed sixty residents in the custody of Qvapu Shervashidze. One elder had been lost". The Catholicos brought out whom he could and settled them in Khobi and Khibula". The names listed are all Megrelian (Georgian). In this way did the Georgians gradually lose their positions in historical Samegrelo (Mingrelia) to the invading Abkhazians. The document just quoted makes the interesting observation that they Catholicos places the Georgian peasants, raided by the Abkhazians, in Shervashidze's care; thus the invading Abkhazians are different from Shervashidze, the latter too seeking shelter from the invaders. The deference gradually became difficult. The Prince Levan Dadiani (1611-16571) of Samegrelo built a special wall to defend the land from the Abkhazians. Vakhushti Bagrationi writes about the wall: "The great Levan Dadiani built a wall to keep the Abkhazians out". On Lamberti's map this wall has a legend indicating that it was for defence from the Abkhazians.

It is worth noting that up to the 17th century, no one differentiated the land populated by Abkhazians socially, confessionally, and culturally from the other population of Georgia as a whole, and of Western Georgia in particular. Foreigners, who supply noteworthy observations, considered Tskhumi a Georgian city. Thus, Abul-Fida, Arab writer of the 12th-13th cent., called Tskhumi a Georgian city, while Pietro Geraldi, Catholic bishop of Tskhumi, in a letter written in 1330 considers Georgians as well as Muslims and Jews as inhabitants of Tskhumi, which means that in Tskhumi of that time there were either no Abkhazians proper or if there were, they did not differ from Georgians in language, religion, and way of life, so that they were taken for Georgians by foreigners. The fact is worth noting that Pietro Geraldi is called Catholic Bishop of 'Lower Iberia'. On 15th century Italian maps we find the legend 'Megrelian port' at the mouth of the Kelasuri river. However, the situation changed by the 17th century. The Italian Giovanni Giuliano da Lucca, who travelled to Western Georgia in 1630, writes: "The Abkhazians are scattered along the sea coast. Their way of life is like that of the Circassians ... . The language of the Abkhazians differs very much from the languages of the their neighbouring peoples. They do not have any written laws, nor do they know how to use writing. By faith they are Christians, without any Christian customs and mores ... . Woods serve them as a cosy shelter. When they have chosen a place to live in they never abondon it. They dress like the Circassians, but their haircut differs from that of the Circassians ... . As they have no other habitat than the woods, their livestock is small and hence they have scanty material for their clothes. They content themselves with wine made from honey, game, and wild fruit. Wheat does not grow in their land. They do not use salt".

According to A. Lamberti, who in the 17th century spent twenty years in Western Georgia, the Abkhazians did not live in cities and strongholds. Several families of the same kin would come together and settle on an elevated place, building thatched huts; for the purpose of defence they would enclose the place with a fence and a moat. It is interesting to note that they were never molested by others, but they attacked and plundered one another.

In the 1640s Georgia was visited by the well-known Turkish historian and geographer Evliya Chelebi, whose description gives a clear picture of the way of life and culture of the Abkhazians of his day. By the time of Chelebi's visit Islam had gained a fairly firm foothold. However, in his words, the Abkhazians "were not familiar with the Koran, nor had they any religion". The foregoing evidence seems to corroborate the opinion expressed in Georgian historiography on the backwardness of Abkhazians at the period under discussion, and on the loss of Christianity. As noted correctly, these authors "were not superficial observers. It was their purpose and obligation to study as thoroughly and precisely as they could the customs and mores, culture and socio-economic development of the peoples they came into contact with, as well as the relationship and difference of these peoples with other peoples, and so on".

What had caused such a change? This question is answered in Georgian historiography. As noted above, in medieval Georgia, an Abkhazian was not considered a non-Georgian. The 11th cent. Georgian historian Leonti Mroveli, in whose work this conception must date from the 7th-8th cent., in speaking about the origin of Caucasian peoples, considers Western Georgia as the land that fell entirely by lot to Egros. Niko Berdzenishvili writes about this conception: "This story is a noteworthy piece of evidence on the ethnic kinship of West-Georgian tribes and their centuries-old historical and cultural cooperation (which is seen so clearly in the light of the evidence of ancient Greek and Latin authors, and especially archaeological data)". Leonti Mroveli was perfectly aware of the existence of the Abkhazians and Abkhazia, but for him Abkhazia was Egrisi. When narrating about Western Georgia, Vakhushti Bagrationi observes that this is a land that was first called Egrisi, then Abkhazia, and then Imereti. For him Western Georgia was equally Egrisi-Abkhazia-Imereti, although he is well aware of the existence of the Abkhazians, and that they have their vernacular. This is accounted for by the fact that historically and culturally they were Georgians, irrespective of their origin.

We have no knowledge of the self-designation of the inhabitants of the Principality of Abkhazia at the time when Georgian historical sources referred to them as Abkhazians. They had their vernacular (at any rate from the 17th cent.). However, since they had neither script nor literature, it is not recorded. It is logical to assume that they called themselves then – as well as now – Apsua. In this connection the question of the language of the Abkhazians (Apsua) arises. In the historical work, tentatively entitled "Histories and Eulogies of the Sovereigns" and forming part of Kartlis Tskhovreba, in connection with the second name, 'Lasha', of Tamar's son Giorgi we find the statement: "which was translated as illuminer of the world /in the language of the Apsars/".

Along with the phonetic similarity of 'Apsua' and 'Apsar', the fact that in modern Abkhazian (the language of the Apsua) 'lasha' ('alasha') means 'clear', 'light' gives ground for the identification of this 'language of the Apsars with the language of the modern Abkhazians (Apsua). However, one point should be borne in mind here. The explanation: 'In the language of the Apsars' is absent in the Queen Mariam (17th cent.) MS of Kartlis Tskhovreba. Nor is it to be found in the Mtskhetan or the Machabeli MSS, the latter MS deriving from the Mariam MS. The explanation figures in 18th cent. MSS, which is duly indicated in the Qaukhchishvili edition.

The author of the Histories and Eulogies writes: "... Lasha, which was translated as illuminer of the world." The 13th cent, historian does not indicate from which language 'lasha' means 'illuminer of the world', whereas the 18th cent, historian and redactor of Kartlis Tskovreba explains that "it was translated from the language of the Apsars".