| The wood is decked in light green leaf. The swallow twitters in delight. The lonely vine sheds joyous tears Of interwoven dew and light. Spring weaves a gown of green to clad The mountain height and wide-spread field. O when wilt thou, my native land, In all thy glory stand revealed? |

The wood is clothed in leaf? The swallow twitters again, In the garden the solitary vinestem Weeps with excess of joy. The mead is in bloom, The mountains blossom, O beloved fatherland Why dost thou not bloom? Ilia Chavchavadze Works Translated by Marjory and Oliver Wardrops Ganatleba Publishers Tbilisi 1987 |

| The full-orbed moon her lustre sheds And floods the land with lambent light. The snowy ridge of distant mounts Dissolves into the heavens bright. Deep quiet holds the breath of night; My mother-land in silence lies, Yet oft is heard an anguished moan As Georgia in her slumber sighs. I stand alone... The mountains, shades, The slumber of my land caress. O God! O God! when will we wake And rise again to happiness? |

The pale light of the full moon Was streaming on the fatherland And its white ray among the mountains Hovered in deep blue space. Nowhere a sound, nowhere a cry Nothing born of parents stirred Save sometimes crying in pain Some Georgian sobbing in his sleep was heard. Again alone... and the mountain's shade Caressed my native land in sleep Still sleep O God! Sleep, always sleep When shalt thou deem us worthy to awake? Ilia Chavchavadze Works Translated by Marjory and Oliver Wardrops Ganatleba Publishers Tbilisi 1987 |

O Georgian mother! Thou gavest sons

To home and land in days of yore.

The future braves were lulled to sleep

With lullabies and mountain lore.

Alas! those days are past, and now

By sorrow is thy country swayed.

Thy very breath of life is fled.

Thy warrior son is now a shade.

Where is the courage of our sires,

The dagger and the crushing blow,

The honour and the pride of old,

The fearless struggle with the foe?

But why should we shed idle tears

For glory that is past and gone;

Another star, O Georgians, must

We find to guide and lead us on.

It is our duty to prepare

The future for the people, and —

Ah here, O mother, is thy task,

Thy sacred duty to thy land:

Endow thy sons with spirits strong,

With strength of heart and honour bright,

Inspire them with fraternal love,

To strive for freedom and for right;

Infuse in them God's Gospel wise,

Give them true courage for the fight,

And thus enrich our land with sons

Who'll change this darkness into light.

O mother! hear thy country's plea:

Nurture thy sons with spirits strong

Led by the torch of truth whose flame

Will banish ignorance and wrong.

|

Beneath the lake of Bazaleti |

Deep down in Bazalethi's lake, 'Tis said a golden cradle lies, And there beneath the welling waves, An orchard blooms, and never dies. That garden gay is always green, Its blossoms never know decay; The changing seasons of this earth, That region rare need not obey. Nor summer's sun, nor winter's cold, Can harm that em'rald orchard gay For, in those sunlit glades of gold, Eternal spring doth hold her sway. In that fair garden's very heart The golden cradle aye doth rest, There man hath never dared to go — That spot has never known a guest Translated by Marjory and Oliver Wardrops Ganatleba Publishers Tbilisi 1987 |

Translated from the Georgian by Marjory Wardrop, London, 1895

I

There, where Mount Kazbek rears his noble brow,

Where eagle cannot soar, nor vulture fly,

Where, never melted by the sun's warm rays,

The frozen rain and snow eternal lie;

Far from the world's wild uproar set apart,

There, in the awful solitude and calm,

Where thunder's mighty roar rules o'er these realms,

Where frost doth dwell and winds sing forth their psalm;

There stood in former days, a house of God,

Built by devout and holy men, the fame

Of that old temple still the folk hold dear,

And Bethlehem is still, to-day, its name.

The ice-bound wall of that secluded shrine

Was hollowed out from craggy, massive block,

And, like an eagle's eyrie on the cliff,

The door stood carved in the solid rock.

Straight downward from this gate unto the path

There hung descending a rough iron chain,

And save by that strange ladder's aid alone

Man could in no wise thereto entrance gain.

II

In days of old, monks left this world of woe.

And there they dwelt devoted unto God,

In that wild wilderness they sang their songs

Of praise, and in the path of saints they trod.

There they withdrew to seek God's solitude,

There they abandoned all earth's vanity,

And, in that everlasting dwelling sought

To fit themselves for God's eternity.

Those holy fathers sacrificed this world,

And, for the pain they suffered in that shrine,

The mountaineers revered them, and they sang

The praise of good deeds, and grace divine.

And by the people still that place is held

So holy, even now, that in the chase

A refuge there the wounded beast may seek,

For there no huntsman dares to leave his trace;

None save the man whose life is given to God

Can rest within that ruin's sacred shade,

And he who breaks this law must perish there

By swift, avenging lightning's trenchant blade.

III

And there, in yon forsaken hermitage,

An anchorite took up his lone abode,

He left the fleeting world and, set apart,

Gave up the present for the life with God.

Far from the dwelling of the sinful man,

Far from the realm where wickedness holds sway,

Where e'en the just man scarcely can escape

From Satan's tempting power; where, night and day,

Man is pursued by evil, like a thief

Which tries to seize upon him unaware;

Where, e'en if right be known by its true name,

The hand of sin will still all evil dare;

Where faithlessness, corruption, rapine dwell,

And brother for his brother's blood doth lust,

Where discord turns the purest love of friends,

By scandal's breath, to hatred and mistrust...

He left that fleeting world where every gift

Is as a snare, and beauty but a lure;

The devil uses even virtues there

To wile th'unwary, and his prey secure.

IV

Alone the hermit dwelt, amid this ice,

A solitary anchorite, his mind

He troubled not henceforth with painful thoughts

Of all the sinful cares of human kind.

He banished from his heart each worldly grief,

Each thought, concern and wish that was profane,

That he might stand before the judgment seat

Of God, with spirit pure and free from stain.

Both day and night, with lamentation, prayer,

And scourging martyred he, for his soul's sake,

His flesh, and, like a vessel wash6d clean,

With tears he strove his spirit pure to make;

Both day and night, with sighing and complaint,

The icy rocks re-echoed forth his groans,

And his fast-flowing, suppliant tears ceased not

In that lone home of weeping and of moans.

Far from this transitory earth apart,

His spirit like a flower there did bloom;

Each worldly wish was calmed and laid to rest,

And all desire was buried in the tomb.

V

He was not old — upon his saint-like face

His soul's nobility was pictured fair,

It could be seen his spirit was the home

Of other thoughts than those of worldly care.

His features melancholy, thin and sad,

Yet beamed with loveliness of grace divine,

Which from his deeply wrinkled, lofty brow,

Like bright encircling halo, forth did shine.

So gentle and so sweet was the deep thought

Expressed in his clear, meditative eyes,

It seemed as if in them was mirrored forth

Virtue herself, arrayed in modest guise;

As if, with gently gladness, they rejoiced

At Paradise's open entrance gate,

Together with his soul, to meet their Lord,

And hastened on, with faith secure, elate.

In fasting and prayer, with body weak,

He lived like holy martyrs who attain,

By many roads of suffering and of woe,

To glory, conquering heroes over pain.

VI

His witness was accepted of the Lord,

Who hearkened to His Humble servant's sighs

And, as a token of His grace, vouchsafed

A miracle in answer to his cries.

In the dark cell wherein the monk did pray

The window faced the dawning day's first gleam,

And downward, in a flood of lustrous light,

The rays of sun and moon did through it stream.

And o'er yon solitary mountain peak

When rose the sun's glad rays of morning light,

Through that small window in his lonely cell

The beam shone down, a column broad and bright.

Lo! when the hermit prayed, it was ordained

That on the ray his book of prayers should stand,

And on that solid sunbeam did it rest

Secure and safe, by God's divine command...

Thus passed his days, and thus rolled on the years,

And as a sign that God approved the way

Wherein he walked, thus pure and without sin,

This wonder was performed day by day.

VII

One evening, from long vigils weary, worn,

Forth through the door he dragged his limbs, and fixed

His meditative gaze upon the plain

Stretched, verdant-carpeted, the hills betwixt.

The setting sun had not yet sunk to rest,

Behind the mountain's summit still he beamed,

And round the peak, like fan of flaming fire,

The heav'ns with a broad-stretching glory gleamed,

Like to a brazier, burned the bright blue sky,

And sparks of yellow and deep crimson-hued,

Glittered among the clouds; bent back by them,

They trembled with a thousand tints imbued.

The hermit was entranced, and raptured gazed —

So wondrous fair, so glorious was the sight —

Upon the splendour of the glowing sun

As on a living picture of God's might...

But suddenly the wind arose; o'er rocks,

Ravines and caverns blew the stormy blast,

And, like a serpent, over Kazbek's peak

A dark low'ring cloud, swift gliding, passed.

VIII

It crept along, tyrannical, immense,

And stretched across the heav'ns' expansive vault,

Then burst the thunderclap, and roared with rage,

As one who doth his deadly foe assault.

The heaven and earth were straight with trembling seized

At that loud noise, that terrible uproar —

Then sudden darkness overspread the sky,

And hissing hail forth from the clouds did pour.

Upon the earth, all intermingled, burst,

With furious din, the thunder, lightning, hail,

The raging wind blew fiercely 'mong the rocks,

With angry whirl, a wild, strong, howling gale;

All these together strove, so that it seemed

As if God oped his vials of wrath, and hurled

An awful judgment down from heaven that day

As retribution on His erring world...

But now the monk took refuge in his cell,

He prayed, with fervently upraised hand,

Before the Virgin's image, that the Lord

From sin and ruin would redeem the land.

IX

Then suddenly, he heard a human voice,

And, startled at this unaccustomed sound,

Again he listened, and he heard beneath

As if one called from out the mirk profound.

Quickly unto the door the hermit ran,

Against the ladder saw a bending form,

And lo! a childish voice cried out aloud

And begged a shelt'ring roof in that wild storm.

Say, can it be a son of man who roams

In this fierce deluge, on this awesome night?

The wild beasts e'en lie cow'ring in their lairs,

In fear they flee the fury of God's sight!

Who art thou?" said the monk, "Art thou a man?

Or evil sprite sent by the devil here?"

"Human am I — I pray thee shelter me!

For God's love, save me now from death's dire fear!

Dost thou not see that heaven is well-nigh rent

And, overwhelming, on the earth doth press?

Is this a time for words! Oh, pity me!

Refuse me not a refuge in distress!"

X

"Thou sayest well. If thou be son of man

'Twere sin to leave thee to the storm a prey;

If thou be spirit ill, then God must wish

To make a trial of His poor monk this day.

Come up whoe'er thou art! God's will be done!

Hold fast this iron chain, and have no fear

It is a ladder safe, footholds there are

By which a man can mount securely here!"

At last he reached the monastery door;

Climbing the steep ascent of that rough chain.

The hermit met him "What or who is this?"

In the deep gloom he asked himself in vain.

"Come in, who'er thou art. I'll shelter thee,

Take refuge here, kneel down and pray,

This is my cell, and lo! it is God's house;

Here many a knee hath bent before this day."

He led the way; into the cell they came;

Here was the darkness deeper, e'en despite

The ashes of the almost burnt-out fire

Which in the gloom gleamed with a feeble light.

XI

Now, when God's Mother let this new-come guest

Into the cell, and showed of wrath no sign,

The monk said in his heart: "'Tis son of man,

And not a spirit harmful and malign!"

The stranger sank down quickly, numbed and wet,

And stirred the cinders, then recumbent lay

Upon the hearth, with both cold hands outstretched,

Over the dying embers' fading ray.

"How cold it is!" exclaimed the shiv'ring guest,

"Ugh! Ugh! I'm frozen into stone!"

The hermit started at the sound, 'twas like

A maiden's voice, he trembled at her moan.

Could it then be that fate had hither sent

This shape in woman's guise to be a test!

And, like a flash of lightning, came this thought

Into the horror-stricken hermit's breast.

But e'en if fate had sent this for a trial,

It must have been by God's own self designed;

Therefore he took it from the Lord in faith,

In confidence and peace of heart resigned.

XII

"Hast thou no firewood?" asked the visitor,

"Go, bring some here and light a fire! A load

Upon my back, to-morrow, will I fetch;

But let me warm myself, for love of God!"

The hermit, from the corner, brought some wood

To light the fire anew; the blaze that beamed

When it was kindled, fast dispersed the gloom,

And through the darksome cell it brightly streamed.

But when the ray, cast from the lighted fire,

Upon the stranger guest, there seated, glowed,

A picture of enchanting loveliness

Unto the hermit's wond'ring eyes it showed.

Full of bewitching beauty, full of life,

A youthful maiden by the fire reclined,

Of noble mien, yet meek, she seemed; her neck

Was bare, and graceful as the timid hind.

The beauty shed abroad from her black eyes

Disputed with the warmth cast by the glow

Of firelight, and beneath that conquering gaze

It yielded up to her, and flickered low.

XIII

The grace of Love herself, if she desired

To picture forth the beauties of her mind,

And if she dwelt incarnate on the earth,

A fairer semblance could not wish to find.

One could not say if grace adorned her form

Or if her form was ornament to grace;

E'en envy, hatred's self, could naught descry —

In that fair maid, of fault there was no trace.

Who would not tremble 'fore her glorious eyes,

Her brilliant cheeks, and bosom heaving high?

Look at her lips!... It seems that Love has left

A kiss imprinted on them tenderly...

Who is not drawn and captivated held

By mighty Beauty's all-enchanting power?...

'Tis said that by its influence subdued

The savage beasts are tamed, and gentle cower.

And e'en that hermit stern, severe and sad,

Grew gentler and more mild, by beauty swayed;

With sorrow in his guileless heart, he gazed,

His eyes held captive by the lovely maid.

XIV

At length he asked her: "Who art thou, my child?

What can have brought thee to this desert drear,

In such rough weather, when the tempest wild

Has almost flooded earth, afar and near?"

"A shepherd lass am I. Down in the lap

Of Kazbek's mount my father's flocks I fed;

Deceived were the sheep by the fresh grass,

I followed them, and on they still were led.

Fair was the evening, when the setting sun

Was glowing, and upon the sky I gazed

Until I could see naught but heaven's vault,

For in its brilliant light my eyes were dazed.

The great sun shone, surrounded with bright rays,

Behind the mountain peak, and heart and eye

Were ravished with the beauty of the sight —

'Twas like God's face that beamed so fair on high.

I quite forgot to heed my father's words:

'My child, trust ne'er yon mountains, for I've seen

The stormy blast sweep suddenly from heav'n,

Although the sun rose glorious and serene'.

XV

"It matters naught! Come," said my eager heart,

'Dost thou not wish this wondrous scene to view?

Intent I gazed... but Kazbek suddenly

Frowned fierce, and clouds o'erspread the heavens blue.

In one brief moment all was darkness drear,

And from the mountain blew a chilly wind.

I wish'd to take the sheep home ere nightfall,

But 'twas too late, the way I could not find.

For suddenly the storm came sweeping on,

Like drops of lead the hail began to shower;

I trembled for the sheep, but could do naught —

In that deep gloom fear robbed me of all power.

Indeed this mountain treacherous is, and false;

For sudden darkness had obscured the day,

The smiling heaven had changed to sudden hell.

And all my joy was turned into dismay.

Ah! why did L not heed my father's words!

What will befall me! Woe is me! They say,

I've heard it oft, that those who disobey

Their father ne'er can prosper in their way.

XVI

"I, disobedient to my father's words,

Had lost the sheep. I only was to blame.

But (canst thou tell me?) how can one avoid

The law that fate inex'rable doth frame?

It was not for the flocks I grieved alone,

'Twas that my father dear would be alarmed —

I am his only child, he loves me much —

Ah! sorely would he grieve if I were harmed.

The sheep were gone — they were his sole support,

His only means of livelihood and gain —

Yet, were I only safe at home once more

He would not frown, lest he should cause me pain.

I stood in that wild storm on yon hillside;

Upon the land, from heaven, the deluge poured,

The mountain shook and trembled to its base

Beneath my feet, while loud the thunder roared. —

What could I do! Where could I hope to find

A shelter from the tempest's raging blast?

Shall I be bold, and strive to reach my home,

Or trust to fate until the storm be past?

XVII

"But if I stay — who knows if I am safe

From this dark night's impending, awful doom!

If I go forth — in some deep, rocky glen

I may be dashed to pieces in the gloom...

Yet I resolved to take the homeward path;

And said: Whatever comes to pass is good!...

Nor canst thou say that I mistook my way;

For here in safety presently I stood.

I felt the chain, and then I knew that this

Must be Mount Kazbek's far-famed, saintly shrine;

Full often had I from my father heard

That here a monk lived for the life divine.

With joy I called aloud, and called again;

My voice was powerless 'gainst the raging wind.

'Woe unto me', I cried, 'if none can hear,

If on this night no shelter I shall find!'

But God had mercy on me, and at last

My cry He carried through the storm to thee —

I need not tell thee more — thou know'st the rest —

May God save thee, e'en as thou hast saved me."

XVIII

"Thanks are not due to me that thou art safe,

For God alone can save the child He made;

He ever stretches forth a helping hand

That He may all His chosen creatures aid..."

"It seems thou thoughtest me a spirit ill!"

"Be not amazed nor troubled in thy mind,

What being in the world would visit me,

A lonely monk forgotten by mankind!"

"Hast thou no ties upon the earth, no friend,

No brother, sister, kin dear to thy heart?"

"These had I once; to all I said farewell.

To serve the Lord, from yon world did I part."

"Hast thou lived here for long?"' "I cannot tell."

"Thou canst not tell!" "My child, from all the fears

Of yon fast-fleeting world apart I dwell.

What reck I of the flight of passing years?"

"And dost thou live without a human friend?"

"To me God's holy will was thus revealed."

"But why should God desire that man should stay

Alone amid these icy rocks concealed?

XIX

"May God not be displeased, nor thou, O monk!

For I am very ignorant in speech...

When in yon vale below I watched my flocks,

And looked up here, as far as sight could reach,

I often pondered o'er my father's words:

'That there a monk dwelt, in those realms of ice,

Who for his soul's sake suffered solitude',

And of his body made a sacrifice.

This tale surprised me, for I could not think

How this should be a pleasing deed to God;

He surely could not be displeased that man

Should love the world where He Himself had trod!

I said within myself: 'How can this be?

'Why did God deck the earth and make it fair

'If man should look upon it as a curse,

'And leave the world and all its beauties rare?

'Should I abandon all, all earthly ties?

'From all my friends, and home, should I depart?

'O God, forgive me! 'tis too hard a task!

'I could not with such ease crush my poor heart!'

XX

"How canst thou bear to leave the world of joy?

Its pleasures sweet thou surely knowest well!

Death sways all here, but there is gladsome life:

Here grief abides, but there delight doth dwell.

Hast thou from thy crushed heart torn ev'ry tie?

Does love no longer linger in thy breast?

Hadst thou not brought grief hither with thee too?

Do care and sorrow ne'er disturb thy rest?

Do dreams of home ne'er haunt the weary hours?

Dost thou ne'er for thy friends and parents pine,

Was there no heart to make thee happy there —

No heart which throbbed in harmony with thine?

How couldst thou leave all love?"... "Hear me, my child!

The soul is dearer than all vain delight;

It is a captive in yon fleeting world,

These joys are chains that stay its upward flight."

"Are all who dwell within the world then doomed?

Must we all hopes of safety then forego?"

"Salvation's road lies open unto all;

This is life's way for me-a way of woe!"

XXI

"A way of woe!" These words he scarce had said

When chilling horror seized the hermit's heart.

Such words betokened bitter discontent —

How could complaint in his calm life find part?

"A way of woe!" 'Twas cry of suff'ring soul

Sunk 'neath the load of sadness and distress —

'Twas like a sobbing sigh, a mournful moan

For joy departed and lost happiness...

What had he lost? Should he not gladsome feel

That from the weary world he had withdrawn,

And all its fleeting fancies flung aside

That for his soul a day of rest might dawn?

It cannot be that still he casts behind

A longing look on life and its delights,

When upward, e'en to God's most holy throne,

Sweet immortality his soul invites.

What had come o'er him? What had moved him thus?

It could not be that now he mourned his fate,

And felt regret that he had yielded all

To Him, who every being did create!

XXII

He dares not own himself displeased with God;

The soul that trusts Him He will never leave.

Was not God's blessing generously given?

He could not wish for more — why did he grieve?

Yea! Yea! His grace was all he could desire...

Then, whence had come those words of deep despair?

Around his cell he glanced, oppressed by fear,

As if perchance some lurking fiend hid there.

But none was there... none save the wearied maid,

Who, sunk in slumbers soft, in silence lay,

While lovingly on her the firelight glowed

And flickered o'er her face, glad and gay.

Bewitching was she as she lay asleep,

Adorned in beauty and all charms of love,

As if, seeking to make her fair and good,

Both love and happiness together strove.

Beauty divine seemed to have shed on her

All the rich treasures of its boundless store,

And, as the nightingale's upon the rose,

So beauty's soul upon her cheek did pour.

XXIII

And when the hermit gazed upon that face

The stormy waves that tossed his heart were still.

Surely some secret force held him enslaved

That he must look on her against his will!

What power is this that o'er him casts its spell?

Is it delight, or sorcery's fell snare?

His eyes were traitors to his mind's command;

He tried to turn away, but still stood there.

Long time he looked... then into his cold heart

At last there streamed a ray, so tender, warm —

He trembled, yet he felt the trembling sweet...

What gape it such a strange and subtle charm?

His agitated heart heaved with quick throbs,

Ne'er had he felt it thus before this day,

He heard the melody of silver strings;

As on a lyre, love on his heart did play-

What meant this sweetness hitherto unknown?

He could not tell this tender feeling's name;

If it was sinful, why was it so like

Immortal life, his soul's incessant aim?

XXIV

A step he took — himself he knew not why —

Calm and serene still slept the wearied maid,

And pleasing thoughts pursued her in her dreams,

While round her parted lips a proud smile played.

And that seducing smile so sweetly hired

Th'enchanted gazer to a fatal kiss,

None could deny those soul-enticing lips,

Not e'en an angel fresh from realms of bliss.

Now, lo! the unhappy monk bent down his head

To kiss her face... but seized with swift alarm

He started back... 'Twas death's delusive snare

That sought to draw him by the maiden's charm.

He was not vanquished? Nay, it could not be

That now his faith had lost its former power —

The thirst for holiness that filled his soul

Would surely last until life's latest hour!

He could not cast away God's holy gifts,

The welfare of his soul and grace divine.

To change them for this earth's harassing cares?

For passing worldly pleasures dared he pine?

XXV

But who is this that calls reproachfully,

"Hast thou not fallen into fatal fault!"

Who cries, triumphant o'er his wounded heart:

"Art thou not vanquished by my first assault?"

Whence comes this sound of noisy, mocking laugh?

What merriment is this that greets his ear?

No one was there; and yet, it could not be

That this loud laugh was born of naught but fear!

And tremblingly, with terror, he looked round;

He was alone… still slept the unconscious maid.

In haste he rose, and, filled with wild alarm,

Before the Holy Virgin bent and prayed.

Is there no help? E'en looking on that face

The same dismay the hermit's heart assails,

'Gainst that curst laughter, fraught with deep reproach,

His erstwhile potent prayer naught avails!

His soul entreats his erring heart to pray,

But all its earnest efforts are in vain;

E'en kneeling 'neath the Virgin's sheltering gaze

He cannot his rebellious will restrain!

XXVI

He looks upon the holy Virgin's face,

His supplicating eyes entreat her aid —

But, woe! her gracious smile beams not on him,

Before him still he sees the shepherd maid.

What brings that form again before his eyes'?

Is it of flesh, or but a phantom pale?

Or has the image of God's Mother changed

Into the likeness of a mortal frail?

Since he has fall'n, does God not deem him fit

To look upon the Virgin's holy face?

Has He performed a miracle divine

To bring His erring servant back to grace?

He tries to cross himself, but lo! his hands

Refuse to move; he seeks to breathe a prayer,

His tongue is mute; he, thirsting for God's smile,

Can see naught save the cursed maiden there.

"Now, canst thou still resist?" and in his cell

The mocking laughter re-echoed forth once more.

No longer could the unhappy monk remain;

But, like a madman, rushed forth thro' the door...

XXVII

...The day was dawning, fair the morning broke,

And from the heav'ns the clouds were chased away,

While o'er the tranquil earth a zephyr breathed

And everywhere peace held her potent sway...

But who is this with wildly waving hair

That runs among the rocks with trembling dread?

It cannot be the monk!... 'Tis he indeed!

O'er his pale face a death-like hue is spread.

See how he stands upon the very brink,

And gazes longingly on yonder peaks,

As if he on those lofty mountain heights

His last and only consolation seeks.

He watches for the sun's first rising ray;

Why doth it tarry? Why doth it delay?

Until this day e'en Time itself was naught,

Why doth a moment now cause him dismay?

— The sun arose! Into his cell in haste

The monk returned, by dawning hope consoled;

For through his window streamed the sun's bright beam,

And stood there like a pillar, massy gold.

XXVIII

His heart was calmed... Once more with timid trust,

His eyes he turned towards the Blessed Maid;

Once more the image smiled upon the monk,

Looking with favour on him as he prayed,

"O God! Thine anger then is turned away!"

And thankful tears forth from his eyes did well.

He laid his book of prayers upon the ray;

But, woe! the unhappy man! alas!... it fell.

Before the hermit's eyes the light grew dim;

Fear seized his fainting heart, and hopeless dread;

With a wild, Availing shriek of woe he fell,

In that bright beam, from earth his spirit fled.

* * *

And there where saints once sang their grateful hymns,

And glorified God's wondrous works and ways,

There where they offered daily sacrifice

Of lamentation, love, and prayer, and praise,

There, midst the landslips and the broken stones,

Only the wind moves to and fro, and sighs

While, fearful of the mighty thunder-clap,

Within its lonesome lair the wild beast cries.

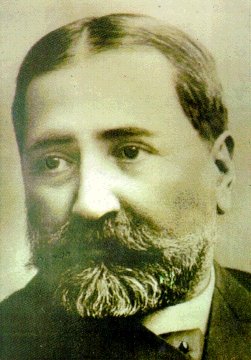

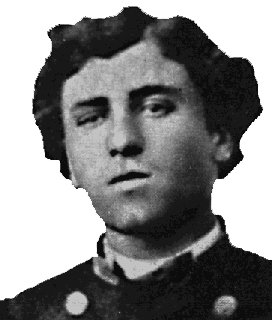

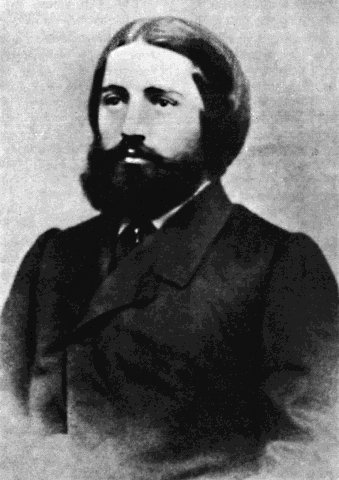

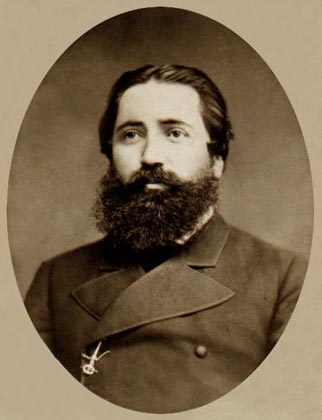

| Autobiography Notes of a Journeyfrom Vladikavkazto Tiflis The Sportsman's Story Is That a Man?! The Hermit (A Legend) King Dimitri's Sacrifice Bazaleti Lake Lines To A Georgian Mother Elegy Spring O our Aragva... The sleeping maid Prince Ilia Chavchavadze (October 27, 1837 – August 30, 1907) was a Georgian writer, poet, journalist and lawyer who spearheaded the revival of Georgian national movement in the second half of the 19th century, during the Russian rule of Georgia. Today he is widely regarded as one of the founding fathers of modern Georgia. He was canonized as Saint Ilia the Righteous by the Georgian Orthodox Church. The Georgian people revere Chavchavadze as Pater Patriae (Father of the Fatherland) of Georgia. Inspired by liberal movements of Europe of his age, as a writer and a public figure Ilia Chavchavadze directed much of his efforts to awakening national ideals in Georgians and building up a firm society in his homeland. Chavchavadze was born in 1837, in Kvareli, Eastern Georgia, to a noble Chavchavadze family. In 1857 he graduated from the 1st Classical Gymnasium of Tbilisi. In 1861 he graduated from the Faculty of Law of the St. Petersburg University. His most important literary works works are: The Hermit, The Ghost, Is a human a man?!, Otaraant Widow, Kako The Robber. He was an editor-in-chief of Georgian periodicals "Sakartvelos Moambe" (1863-1877) and "Iveria" (1877-1905), and authored numerous journalistic articles. Most of his work deal with Georgia and the Georgians. He stood as a devoted defender of Georgian language and culture from Russification. Chavchavadze was killed by a gang of assassins in Tsitsamuri, outside Mtskheta. His legacy earned him a broad admiration among the Georgians. Ancestry and early life Ilia Chavchavadze was born in Kvareli, a village located in the Alazani Valley, Kakheti province of Georgia, which was part of the Russian Empire during that time. Ilia was a tavadi, a Georgian noble title of prince. Supposedly, the noble last name of Chavchavadze came from Pshav-Khevsureti region of Georgia and in 1726, King Constantine I granted Chavchavadze family the status of the Princes on account of their knighthood and valor to the nation. This has resulted in their migration and re-settlement in the Alazani Gorge, Kakheti. According to King Erekle II's order Ilia's great grandfather, Bespaz Chavchavadze was awarded knighthood when he defeated twenty thousand Persian invaders in Kvareli in 1755. Ilia was a third son of Grigol Chavchavadze and Mariam Beburishvili. Grigol, like his father and his famous ancestors had a military background. He with the local militiamen protected the village from numerous Dagestani invasions. This, in fact, can be seen from the architecture of Ilia Chavchavadze's museum house in Kvareli, incorporating Medieval castle style in the two storey castle in the yard, which was designed to protect the house during the invasions. Ilia's mother Mariam died on May 4, 1848, when Ilia was ten years old, and his father asked his sister Makrine for assistance in bringing up the children. aunt Makrine had a significant impact on Ilia's life, because after 1852, when Ilia's father Grigol died, she was the only caretaker of the family. Chachavadze was educated at the elementary level by the deacon of the village before he moved to Tbilisi where he attended the prestigious Gymnasium for Nobility in Tbilisi in 1848. However, since an early age Ilia was influenced by his parents who were highly educated in classical literature, Georgian history and poetry. The inspiring stories of Georgian heroism in the classical historic novels was exposed to Ilia through his parents. In his autobiography, Ilia mentioned his mother Princess Mariam Chavchavadze who knew most of the Georgian novels and poems by heart and encouraged her children to study them. Ilia also mentioned about the influence made by the deacon's story telling which gave him an artistic inspiration, later applied during the composition of his novels. In 1848, after the death of Princess Chavchavadze, Ilia was sent to Tbilisi by his father to start the secondary education. At first, Ilia attended a private school for three years before he entered the 1st Gymnasium of Tbilisi in 1851. Soon after, Ilia's father died and the aunt Makrine took all the responsibility of the family. His secondary school years were very stressful for Ilia, due of his father death. However, the Chavchavadze family suffered another devastating blow when the Ilia’s brother Constantine was killed during the Dagestani raid on Kakheti. Ilia expressed his stress and grieve in one of his first short-poems called Sorrow of a Poor. In addition to the personal problems, the political situation was worsening in Georgia under the harsh authority of the Russian Empire which has played a destructive role for nation and its culture. Student years After graduating from the Gymnasium, Ilia decided to acquire a higher education in the University of St. Petersburg, Russia. Before leaving for St. Petersburg, Ilia composed one of his most remarkable poems, To Mountains of Kvareli in the village of Kardanakhi on April 15 of 1857, where he expresses his admiration to the Greater Caucasus Mountains since his childhood and his sorrows for leaving the homeland. The same year Ilia was admitted to the University of St.Petersburg. During his student years at St Pitersburg, numerous revolutions sprung up in Europe which Ilia observed with great interest. Ilia attention focused on the events in Italy and the struggle of Giuseppe Garibaldi whom he admired for many years. While in St.Petersburg, Ilia met with Princess Catherine Chavchavadze, from whom he learned about the poetry and lyrics of the Georgian romantic Prince Nikoloz Baratashvili. Due to the harsh climate in St Pitersburg, Ilia became very ill and returned to Georgia for several month in 1859. Ilia finally returned to Georgia after the complition of his studies at St Pitersburg in 1861. While on his journey back home , Ilia wrote one of his greatest masterpieces The Travelers' Diaries, where he outline the importance of the nation-building and provided an allegorical comparison of Mt. Kazbegi and the Tergi River in the Khevi region of Georgia. Political life Newspaper "Iveria" (Iberia) founded and edited by Chavchadze during his political career. The Newspaper focused on national-liberation movement of Georgia in late 1800s. Ilia’s main political and social aims were embodied in Georgian patriotism. He radically advocated the revival of the use of the Georgian language, the cultivation of Georgian literature, supporting the revival of autocephalous status for Georgian national church and finally the revival of Georgian statehood, which had ended when the country became part of the Russian Empire. As supporters of his ideas grew, so did the opposition among the leading Social-Democrats and Bolsheviks like Noe Zhordania. Their main aims were concentrated in battling Tsarist autocracy and implementing Marxist ideology all over the Russian empire. This did not include the national revival of the Georgian state and of Georgian self-identity. Ilia was viewed as bourgeois and as an old aristocrat who failed to realize the importance of the revolutionary tide. In addition to his works described above he was also the founder and chairman of many public, cultural and educational organizations ("The Society on the Dissemination of Literacy Among Georgians", "The Bank of the Nobility", "The Dramatic Society", "The Historical-Ethnographical Society of Georgia", etc.). He was also a translator of British literature. His main literary works were translated and published in French, English, German, Polish, Ukrainian, Belarusian, Russian and other languages. From 1906 to 1907 he was a member of the State Council (Gosudarstvennaya Duma) of the Russian Empire. His eclectic interests also led him to be a member of the Caucasian Committee of the Geographical Society of Russia, the Society of Ethnography and Anthropology of the Moscow University, the Society of Orientalists of Russia, the Anglo-Russian Literary Society (London), etc. Assassination of Ilia After being a member of the Upper House in the first Russian Duma, Ilia decided to return to Georgia in 1907. On August 28, 1907 Ilia Chavchavadze was murdered by the gang of six assassins who ambushed him and his wife Olga while traveling from Tbilisi to Saguramo, near Mtskheta. The assassination of Ilia Chavchavadze remains controversial. Based on recent discoveries in archives and documents, the plot to assassinate Ilia was masterminded by the co-operation between Social-Democrats and the Bolsheviks due to Ilia's condemnation of their revolutionary ways and his tremendous popularity and trust among the people. During World War II, an old man confessed of being hired by Russian gendarmerie to assassinate Ilia. During the Soviet period, an investigation was launched by the Soviet authorities which later came to the conclusion that the Tsarist secret police and administration had been involved in the assassination. Either way, the assassination of Ilia became a wide-scale national tragedy which was mourned by the entire country and by Georgian society. Prince Akaki Tsereteli, who had serious health problems, spoke at the funeral and dedicated an outstanding oration to Ilia: “Ilia's inestimable contribution to the revival of the Georgian nation is an example for the future generations”. In 1987, he was canonized by the Georgian Orthodox and Apostolic Church. Legacy As the result of Ilia's death, Bolshevik terrorism was rising while Georgian Social-Democrats started to gain significant power and support among the population. Eventually, realizing their differences with the Bolsheviks, the Social-Democrats of Georgia decided to revive Georgian statehood and proclaimed the independence of Georgia on May 26, 1918. After the Bolshevik occupation of Georgia and her integration into Soviet Union, Ilia became a national symbol of Georgian freedom and national liberation. During the anti-Soviet protests in Tbilisi of 1989, poems, novels and the political life of Ilia Chavchavadze became a driving force behind the Georgian strive toward independence. National revival, which Ilia preached and advocated in various Georgian societies during his life, gained its momentum in 1990. |