Georgian film history began in late 19th century and the first cinema opened in Tbilisi in 1896; by the 1900s, there were several film theaters throughout Georgia. In 1912, Vasili Amashukeli and Alexander Digmelov directed the first documentary film Akaki Tsereteli Racha-Lechkhumshi, which effectively marked the begining of the Georgian film industry. In 1916, Alexander Tsitsunava made first feature film Kristine. After World War I, Tbilisi was second only to St. Petersburg in a number of cinema theaters and film productions in the Russian empire.

The Georgian film industry prospered in the 1920s, when a special unit was established at the Commissariat of People’s Education in 1923 and later developed into Goskinprom (state cinematic production). This period produced several talented directors. Siko Dolidze’s Dariko, David Rondeli’s Dakarguli Samotkhe, Kote (Konstantine) Mikaberidze’s Chemi bebia, Nikoloz Shengelaia’s Eliso and Narinjis Veli, Ivane Perestiani’s Arsena Jorjiashvili and Krasnie diavoliata, Amo Baknazarov’s Poterianoe sokrovishe, and Mikhail Kalatozov (Kalatozishvili) Marili Svanets set standards in the industry and greatly influenced subsequent generations of Georgian artists. In the same period, Alexander Tsutsunava and Kote Marjanishvili, both coming from a theatrical background, introduced the best traditions of dramatic art into the Georgian cinema. Tsutsunava’s most memorable films were Vin Aris Damnashave? and Djanki Guriashi while Mardjanishvili’s Samanishvilis dedinatsvali remains one of the finest Georgian comedies. In 1929, Mikhail Chiaureli debuted with Saba and later produced his other feature film Khabarda.

As the Soviet authorities strengthened, the Georgian film industry found itself increasignly under pressure to conform with official guidelines. Socialist realism became the dominant theme and the creative force gradually weakened. This was especially evident between the 1930s and early 1950s, when the cinema effectively became a propaganda machine for the Soviet leader Joseph Stalin. In 1938, the Tbilisi Cinematographic Studio was established in Tbilisi. Several Georgians rose to prominence in this period, notably Mikheil Chiaureli who emerged as one of the most important Soviet filmmakers in the 1940s and became Joseph Stalin’s favorite director; his movies contributed significantly to the creation of Stalin’s personality cult. Among his important works were Velikoe Zarevo (1938), Giorgi Saakadze (1942-1943), Kliatva (1946), Padenie Berlina (1950), Nezabivaemii god 1919 (1952), etc. The success of the Georgian cinema was also due to a generation of talented artists, including Nato Vachnadze, Veriko Anjaparidze, Alexander Zhorzholiani, Sergo Zakariadze, Tamar Tsitsishvili, Ushangi Chkheidze, etc. Mikhail Gelovani became famous for his portrayal of Joseph Stalin in Vyborgskaia storona and Lenin v 1918 (1939), Oborona Tsaritsyna (1942), Kliatva (1946) and Padenie Berlina (1950).

In the 1950s-1960s, the Georgian cinema saw the establishment of the Gruzia Film studio and the rise of a young generation of talented directors and screenwriters. Tengiz Abuladze and Rezo Chkheidze collaborated on the 1954 feature film Magdanas Lurja, which earned them the prestigious Golden Palm at the Cannes Film Festival and first prize at the Edinburgh International Film Festival in 1956. Abuladze’s other film Someone Else’s Children (1956) won awards at the international film festivals in Tashkent, Helsinki, London and Tehran. In 1958, Mikhail Kalatozov (Kalatozishvili) achieved great success with his Letiat zhuravli that won the prestigious Palme d’Or at the Cannes Film Festival and he went on to direct the successful films Neotpravlennoe pizmo (1959) and Red Tent (1969).

The period between the late 1960s and the 1980s was the golden age of the Georgian film industry, which produced up to 60 films a year. In 1972, the Faculty of Cinema was established at the Shota Rustaveli Institute of Theater and later developed into the Tbilisi Institute of Theater and Film. The studio employed such prominent directors as Giorgi Danelia, Eldar and Giorgi Shengelaia, Otar Ioseliani, Lana Gogoberidze, Mikhail Kobakhidze, Nana Jorjadze, Dito Tsintsadze, Sergey Paradzhanov, Goderdzi Chokheli and others. The period is noteworthy for a remarkable collaboration of the creative artists Rezo Gabriadze and Eldar Shengelaia, who produced such memorable films as Arachveulebrivi gamofena (1968), Sherekilebi (1973) and Tsiferi mtebi (1983). In 1962, Abuladze produced one of his most popular feature films, Grandma, Iliko, Illarion And Me, based on Nodar Dumbadze’s novel. One of the most acclaimed Georgian films of this period Otets soldata was directed by Rezo Chkheidze in 1964, with Sergo Zakariadze in the leading role. Chkheidze went on to direct a series of hits, including Gimilis bichebi (1969), Nergebi (1972), Mshobliuro chemo mitsav (1980), Tskhovreba Don Kikhotisa da Sancho Pansasi (1988). Abuladze’s Vedreba (1967) won a grand prix at the San Remo Film Festival while his other film Natvris Khe (1976) was also honored at film festivals in Riga, Tehran, Moscow, etc. Giorgi Shengelaia directed the popular movies Pirosmani (1969), Matsi Khvitia (1966), Alaverdoba, Rats ginakhavs, vegar nakhav (1965), Khareba da Gogia (1987), Sikvaruli Kvelas unda (1989) and the musical Veris ubnis melodiebi (1973). Ioseliani worked on Giorgobistve (1968), Iko shahsvi mgalobeli (1970) and Pastoral (1975) while Kobakhidze produced Kortsili (1964), Qolga (1966) and Musikosebi (1969). Lana Gogoberishvili achieved critical acclaim with Gelati (1958) and later directed Me vkhedav mzes (1965), Peristsvaleba (1968), Rotsa akvavda nushi (1972), Aurzauri salkhinteshi (1975), Ramodenime interviu pirad sakitkhze (1979) and Oromtriali (1986). This period is also noteworthy for a number of short films, including Kvevri, Serenada, Ghvinis Kurdebi, Peola and Rekordi, that remain popular to the present day. Goderdzi Chokheli directed Mekvle, Adgdgoma, Adamianta Sevda, Utskho, Agdgomis Batkani and Tsodvis shvilebi. In 1979, Temur Babluani made a debut with Motatseba and followed with Begurebis gadaprena (1980) and Kukaracha (1982).

Some of the films produced in this period were censored and kept from public release. Otar Ioseliani’s works were suppressed on several occasions, while Abuladze’s famous Monanieba (1984) was released only three years later. This feature film of Abuladze became one of the most famous and controversial movies of this period as it portrayed the brutal reality of Stalin’s purges and had a long-lasting effect on raising political consciousness in the Soviet Union. Sergey Paradzhanov was another major director in the Georgian cinema, whose works earned him worldwide acclaim. His Shadows of Our Forgotten Ancestors (1965) became a breakthrough film and international success, garnering the British Film Academy Award in 1966. His next film, Sayat nova (The Colour of Pomegranates), revealed his mastery of film art and complexity of his vision that produced a series of unforgettable scenes. In 1980s, Paradzhanov directed two major films Legenda o Suramskoi kreposti (1985) and Ashik Kerib (1988) that further enhanced his stature as the preeminent Soviet director of his generation.The Georgian film industry fell in disarray in the early 1990s, when Georgia found itself in the midst of a civil war, ethno-territorial conflicts and economic crisis. Nevertheless, a number of popular films were produced, including Laka, Gamis Tsekva, Zgvarze, Isini, Ara, Megobaro, Otsnebata Sasaplao, Rcheuli, Ik Chemtan, Ak Tendeba and others. Babluani directed Udzinarta Mze in 1992 and won the Silver Bear prize at the Berlin Festival. Dito Tsintsadze debuted with Dakhatuli tsre in 1988 and later produced Sakhli (1991), Stumrebi (1991) and Zghvarze (1993). Many directors emigrated to Europe and Russia. Otar Ioseliani and Mikheil Kobakhidze continued their career in France while Nana Jorjadze and Dito Tsintsadze worked in Germany; Jorjadze enjoyed a very successful career, winning the Caméra d’Or at Cannes for her Robinzoniada, anu chemi ingliseli papa (1986) and receiving a nomination for the American Academy Award for her Les Mille et une recettes du cuisinier amoureux (The Chef in Love, 1997). In 2001, the National Center of Cinematography was established in order to revive the Georgian film industry. An international film festival had been organized annually in Tbilisi since 1999. Unfortunately, a massive fire in mid-January 2005 destroyed a large number of the Georgian movies after the storehouse of the Georgian Film Studio burned down in Tbilisi.

Alexander Mikaberidze

In Georgian mythology, Amirani is a hero, the son of the goddess Dali and a mortal hunter. According to the Svan version, the hunter’s wife learned about her husband’s affair with Dali and killed her by cutting her hair while she was asleep. At Dali’s death, the hunter extracted from her womb a boy whom he called Amirani. The child had marks of his semi-divine origins with symbols of the Sun and the Moon on his shoulder-blades and a golden tooth.

Georgian myths describe the rise of the titan Amirani, who fights devis (ogres), challenges the gods, kidnaps Kamar (the daughter of gods), and teaches metallurgy to humans. In punishment, the gods (in some versions, Jesus Christ) chain Amirani to a cliff (or an iron pole) in the Caucasus Mountains, where the titan continues to defy the gods and struggles to break the chains; an eagle ravages his liver every day, but it heals at night. Amirani’s loyal dog, meantime, licks the chain to thin it out, but every year, on Thursday or in some versions the day before Christmas, the gods send smiths to repair it. In some versions, every seven years the cave where Amirani is chained can be seen in the Caucasus.

Scholars agree that this folk epic about Amirani must have been formed in the third millennium BCE and later went through numerous transformation, the most important of them being morphing pagan and Christian elements after the spread of Christianity. The myth could have been assimilated by the Greek colonists or travelers and embodied in the corpus of the famous Greek myth of Prometheus. In the Georgian literature and culture, Amirani is often used as a symbol of the Georgian nation, its ordeals and struggle for survival.

Epic

AMIRANI

I

There was and there was not (of God's best may it be!), there was an old hunter, named Sulkalmakhi. He lived in a forest with his wife Darejan and his two little sons, Badri and Usupi. His eldest son Tsamtsumi lived in a distant country.

One evening, on his way home, after a weary day of hunting, he came to a high cliff. As it was late, he spent the night in a cave near this cliff. At dawn he heard a scream that came from the top of the cliff. After much difficulty, he reached the top. And there, in a cave, he beheld Dali, the Goddess of the wood (hunt). She lay writhing on the ground. The Goddess on seeing him begged him to take a knife and cut open her womb and take from it the baby that

was there. She told him that a stranger had come to her while she was sleeping, and had cut off her long golden hair, and had remained with her that night-"If it be a boy, name him Amirani. Take him, and bring him up and love him as thine

own." The hunter did as she told him. He cut open her womb with his knife and took out the infant. It was a boy who" had a golden tooth in his mouth. The hunter took the infant home to his wife, who soon loved him even more than her

own sons, so that he was called "Darejani's son". Amirani grew as much in a day as other children grow in a year.

II

Soon the hunter and his wife died, leaving the children to look after themselves. As for Amirani

Astounding was the quantity of wine he drank and food he ate.

For dinner he a bull devoured; for supper more than three he ate.

Now Badri was as gentle and as lovely as a virgin maid.

A crystal tower did Usup seem, so strong and graceful was he made.

But like a dark and lowering cloud was Amirani, ever grave.

Once Amirani and his brothers went ahunting far from home.

O'er many mountains did they wander, over plains where devils roam.

They passed the Algetisni mountain, heeding neither heat nor cold,

When sudden from its lofty summit sprang a deer with horns of gold.

Upon this strange and distant mount they saw a crystal castle fair.

They walked around the lofty tower, but could not find an entrance there,

Then Amirani struck the wall on which the sun its light did pour;

And there the castle oped its mouth, and lo! before them stood a door.

A warrior dead upon the floor, and near his head a steed they spied;

At his right side a giant sword sent flashing lustre far and wide.

His shield reached heavens high, and tore the lining of the spacious sky;

And in one corner of the room in heaps did gold and silver lie.

With loosened hair his mother knelt, and for her child she loudly cried.

His wife whose tears o'erflowed the seas sat weeping at her husband's side.

The dead man held a letter in his hand, which he had written before his death. Amirani, stooped down, took it and read aloud...

"I beg of ye, to list to me. Usup's brother's son am I.

All trembled at my strength and might; the foe from me in fear did fly

Yet while the devi Baqbaqi is alive, no peace have I,

So, whoe'er slays that monstrous giant to him my flashing shield give I;

Whoever brings the tidings glad to him my peerless sword give I;

Whoe'er my parents buries well to him my wealth and land give I;

Whoever finds my sister's fate to him my hoard of gold give I;

Whoever buries me to him my wife and faithful steed give I."

On hearing this the brothers were greatly troubled, for it was then that they learned of

the brother whom they had never seen or known of. Amirani was the first to speak. "Why do we

stand here doing nothing. Let us go and seek the devi Baqbaqi. But wait, let us take away the

lady, the steed and all this gold and silver before we go."

But the brothers said:

"O Amirani of the sun, desire not that what is not thine.

Else thy good name be spat upon for robbing a dead man's riches fine."

They buried the dead and locked the castle. Then they set out to find the devi. Soon they met the devi Baqbaqi who had heard of Tsamtsumi's death, and was coming to eat him.

But Amirani rushed upon the devi with his sword on high.

"No Christian wilt thou touch," he cried, "thou monster vile, I dare thee try!"

Then Amirani and the giant to all the world their strength disclosed.

Their cries like thunder echoed far as both in deadly struggle closed.

The devi felt his strength give way and down he fell upon the plain.

His arm was cleft, he howled aloud as on the ground he rolled in pain.

"Darejani's son," he cried, "O kill me not, I beg of thee!

And I shall tell thee of a maid who lives beyond a magic sea.

So fair is she that ev'n the sun has never seen the like before.

Her dress is made of wondrous silks and gold that sunbeams o'er it pour.

But one must pass great seas and mounts to reach Qamari's native strand.

I'll give to thee a cunning slave to help thee find that distant land."

Amirani wished to let the devi go free, but his brothers said: "Kill him, otherwise thouwilt regret it."

The devi had three heads. Amirani, listening to his brothers' words, cut off Baqbaqi's heads. But before he had cut off the third the devi said: "One thing I ask of thee before I die. Do not kill the three worms that will crawl out of my heads."

Amirani cut off the third head. From Baqbaqi's heads three worms crawled out. Usupi told Amirani to kill them at once, but Amirani laughed and said: "The devi could not do me any

harm, so can three tiny worms do anything to me?" Then he turned to the guide Baqbaqi had given them and told him to lead the way to Qamari, a maid such as the sun had never seen the like of.

Thus they went over hill and vale, without a rest, without delay,

Hoping to reach the destined place at close of every weary day.

They followed e'er the wary guide, and thus went on an endless way.

But soon the brothers understood the guide was leading them astray!

Then Amirani shouted loud: "Thou wretch, I'll make thee howl in woe.

Mislead us not or else I'll strike thee flat upon the ground below."

The guide soon led them to a plain where they beheld in dread dismay

Baqbaqi's worms to dragons three had grown and there before them lay!

One worm was red, the other black, the third was white; and all the three

Sang: "Amirani do we seek," as they came prancing o'er the lea.

"Come, brothers mine, and let us kill the dragons!" Amirani cried.

"Thou didst not kill the worms; so fight alone the dragons," they replied.

Then Amirani clutched the sword that like the wrath of heaven flashed:

"Help me in my distress, my sword!" and towards the dragons three he dashed.

A dreadful struggle took place. Amirani killed the white dragon. Then he killed the red one. The black dragon rushed forward belching fire and smoke. Amirani was so exhausted and weak that the monster swallowed him, and off it went to its mother, the sea. Usupi and Badri were greatly distressed. They resolved to kill the dragon. Usupi drew his bow and lo! the dragon's tail was severed off. The monster wished to wind itself about a tree and crush its prey. But it strove in vain and could only flap the stump of its tail on the ground. The dragon groaned: "O mother, help! my entrails burn and render me wild!"

"None but the son of Darejan can ever harm thee, dearest child."

"He who is in me has a tooth of gold." the dragon writhing sighed.

"Woe to thy mother and to thee, for that is Darejani's child!"

In the meantime Amirani had taken out a sharp knife which he had in his boot. He cut through the dragon's belly, and came out. Once again the three brothers set out in search of Qamari. They went on and on beyond the sky, across the earth, through forests, across the plains, over the mountains, through storm and battle and through fire and blood. At last they came to a large castle where nine devis lived together with their wives and children. It was impossible to count the number of their sons and daughters and grandchildren.

Then Amirani rushed within and killed the devis at one blow.

Blood flowed and overflowed the house; the world gleamed in a crimson glow.

The blood rose up and filled the tower, and Amirani felt the dread

Of being drowned within the sea of blood that now had reached his head!

But suddenly his eyes beheld a struggling devi floating nigh;

He caught and threw it at the door, which opened wide, and with a cry

The blood rolled up, and like a ball of thunder left the castle high.

The brothers came into the tower and found a mount of devis dead.

They cleared the house and washed the floor which devis' blood had stained with red.

And thereafter the brothers three a life of peace and comfort led.

IV

Thus Amirani and his brothers lived happily together for some time. But, as time passed, Amirani grew sad. The thought of Qamari, the maiden unseen even by the sun, was ever in his

mind. He grew restless. So one day he turned to Badri...

"Give me thy steed Snow-white," he said, "'twill lead me safe o'er land and sea;

We'll fly along the tempest's breast, and bring Qamari back with me."

Badri gave him his steed Snow-white. Amirani together with his brothers went forth to find Qamari. Soon they came to a great sea. Amirani, leaving Usupi and Badri on the shore plunged into the sea. Snow-white cut through the waves and Amirani in the twinkling of an eye found himself on the opposite shore, where Qamari lived.

Qamari's parents lived amidst the suns and stars in heavens high;

Above the world their castle fine hung swinging in the azure sky.

Then Amirani spurred his horse, and like an arrow made it fly;

And with his sword he cut the chain that tied the castle to the sky.

The castle fell, and Amirani to the window rode and cried:

"Qamari, come, and be my wife, in happiness with me abide."

Qamari was tidying up the house when she heard Amirani call. "Thou must wait," she replied, "I must wash these dishes before I go with thee." Amirani tied his horse and went in. The beautiful maiden asked him to help her.

He placed each dainty dish upon a shelf. But one little dish would not stand upright.

He tried and tried and tried in vain, he tried with all his might and zeal;

And then impatiently he threw it down and crushed it with his heel.

Then piece with piece, and dish with dish, began to speak in deafening cry;

And all the dishes upwards flew to Qamari's father in the sky.

Qamari told Amirani to make haste for — "If my father finds us here, to escape his anger will be late." So Amirani and Qamari rode away in great haste... The whirling winds in fury blew; the rain like torrents flowed from high. But Amirani wondered much to see the sun shine in the sky. "The wind," explained Qamari, "is the dust blown up by the rushing feet of my father's men. The rain is the tears shed by my mother who is weeping for me. But Amirani, quick, lest we be overtaken."

"My Qamari," answered Amirani, "why this haste? Fear them not.

No tiny forest bird am I caught by a falcon when on high;

No rabbit caught by dogs am I; no little leaf wind-tossed am I.

My brothers two and I will cut the heads of all the coming foe,

And all thy father's men I'll lay stone dead before thee with one blow.

So let them come! Let thousands come! I'll meet them with my dagger bright.

However great their number be, however great their strength and might."

Amirani and Qamari soon reached the shore where Usupi and Badri were waiting. They looked back and saw the sea covered with ships sent by Qamari's father. The ships were full of devis and Kajis. Usupi mounted the steed Snow-white and plunged into the sea. He fell upon the Kajis and devis and killed half their number. But he was wounded and fell dead. Now Badri rushed at the enemy, and hewed and hacked them down. But he also fell wounded and died.

Amirani shot an arrow, but before following it cried:

"Far better than a shameful life is gloried death within a grave!"

Now Amirani forward rushed and made the foe before him fall;

But there was one whom none could kill, the strongest, mightiest of them all.

The lord of the devis and Kajis was Qamari's father, who was wroth to see all his army slain. He rushed in fury and anger at Amirani. Fire lighted up the sky as sword met sword. They

struggled a long time, but neither could strike the other. Qamari saw with a sinking heart that Amirani was about to fall. She knew that it was impossible to kill the lord of the devis and Kajis. She called to Amirani:

"Thou fightest not as warriors should," and tears flowed from her anxious eye.

"Strike lower down to bring him down! Thy sword thou wieldest up too high."

"A house that's shattered at the base will fall, however large or high."

Her father on hearing her words cried:

"Cursed be the hussy! Hear her words! How to her father she is blind.

Like leaves do husbands thrive, but can she another father find?

Why did thy mother care for thee. It would have been better if she had brought forth a dog instead, for it would have been more faithful and true to her."

"I never sucked my mother's breast, nor ever heard a lullaby;

None cared if I lived on or died, alone, abandoned I would cry."

When Amirani heard the words he swung his mighty sword around,

And in one lightning stroke his foe, deprived of life, fell on the ground.

Amirani, victorious and happy hurried back to Qamari. But on the way he met a woman. She said to him: "Where goest thou? Why this haste? For thy beloved thou hast slain her father and his men. But who is grateful to thee for the deed? If thou wert a man thou wouldst unsheathe thy steel, and find thy brothers." Amirani suddenly remembered Usupi's words, "For thy lady love thy brothers are willing to die." Amirani forgot Qamari. His only thought and desire was to find Usupi and Badri. He said to himself, "If I find my brothers alive, I will rejoice and be happy with them, but if they are dead, I will dig a grave, and lay myself beside them."

On the fields covered with the bodies of the devis and Kajis vultures and beasts of prey were feasting and revelling. After a long search Amirani found the dead bodies of his brothers.

"O brothers mine," he wailed aloud, "Hear how I mourn for you and cry.

Have pity! be not wroth with me; to ye I come; with ye I die."

He tried to plunge into his heart his dagger, but in vain the strife;

He knew not that if he had cut his little finger with a knife,

Then he would bleed to death and thus, with gladness, leave this woeful life.

But Amirani knew this not, so down he sat and grieving said:

"Unworthy am I ev'n of death." And on the ground his dagger laid.

But one dead Kaji sudden sat, and to the other Kajis said:

"O Kajis, listen to me now and know of what the world is made.

You hear how Amirani weeps and grieves because he cannot die;

If he cuts off his finger then the blood will flow and he will die."

On saying this the Kaji lay down again. All was as still as before.

Amirani, who had heard the words of the dead Kaji, took his dagger and cut his little finger off. The blood flowed out and he lay down beside his brothers. "Qamari," he whispered weakly, "give up thy life for me, and die with me. Prefer me

dead to even the glory of a living lion."Amirani breathed his last. Qamari with loud wailings ran up to him. With loosened hair, she mourns her mate; her tears with seas and oceans blend. In pity leaves from trees drop down, and to her wailings rustlings lend. At that moment there jumped out a little mouse. It began to lick Amirani's blood but Qamari in rage took off her shoe and throwing it at the mouse killed it.

At this the mother of the mouse came out and to Qamari said:

"Thou wanton, for thy love and sake thy mate and all thy kin are dead.

Thou canst do naught for all thy dead, while I can bring my child to life."

When both the mice had disappeared within their holes beneath the ground,

Qamari rose with beating heart, and soon that very herb she found.

Qamari applied it to Amirani, and he was restored to life. When he saw Qamari he said: "What a long time I have slept!" But Qamari said: "Thy sleep would indeed have been a long one but for the mouse." She told him what had happened. Then she applied the herb to Usupi and Badri. They both came back to life.

Then all the four, Qamari, Amirani, Usupi and Badri went home rejoicing.

O happy they, three brothers true, for whom the golden sunbeams glow;

Their wives none dare to carry off, none dare to face their deadly blow;

None dare to break within their homes, nor to their lives bring grief and woe.

V

Thus they lived happily. Amirani was always in search of new adventures. He killed many giants and dragons. And the wonder of his deeds spread throughout the world. For fear of

him no bird flew under heaven, no ant crawled on earth. And soon there were but three devis, three wild boars, and three oak trees left standing in the world.

Many times had Amirani offended God but had always been forgiven, nevertheless — Amirani, who had nowhere met his match, became so confident of himself, that he desired to try his strength with his Godfather, Jesus Christ.

So once when Jesus Christ stood before him he expressed his desire to wrestle with Him. Jesus Christ said that it was a sin to fight with one's Godfather. But Amirani would not be

persuaded and wishing to test. His strength challenged his Godfather to wrestle with him. "Very well, have thy wish." said Christ. He waved a large stick above His head, and driving it deep into the ground, told Amirani to pull it pout. Amirani pulled, and with one hand drew the stick out. Then his Godfather drove another stick into the ground. Again did Amirani draw it out.

"Art Thou playing with me?" he asked angrily.

"Try to draw this one out," said Jesus Christ.

And saying this He swung His stick and fixed it firmly in the ground.

The stick took root which grew so long that soon about the world it wound.

Amirani could not pull the stick from the ground. Then Jesus Christ cursed Amirani. Upon the highest peak of the Caucasus He stuck a huge iron pole, and bound Amirani to it with a chain. He left a black-eared dog with Amirani, for the dog had killed many deer loved by God. A vulture had given it birth, so that it had wings. Every day a raven brought to them a loaf of bread and a glass of wine. Amirani and the dog pulled ceaselessly at the chain the whole year

long; The pole was almost out when lo! a bird would perch upon its top. Amirani knew that the bird was sent by God, and wishing to kill it, he flung a large iron hammer at it. The bird flew away in time to avoid the hammer.

The hammer strikes the iron pole which sinks into the ground again.

And every year do Amirani and the dog pull at the chain.

The chain thus strained at soon wears out and when about to break in twain,

The blacksmiths of the world come there and quickly make it whole again.

And Amirani's dagger lies beside him on the ground below;

But rust hath eaten up its blade; no more doth it with lustre glow.

"God forbid!" every Georgian prays, that Amirani ever break the chain and become free "He will first kill all the blacksmiths, and then dare defy even God."

Let woe be far, and joy be near; chaff be there, and flour be here;

God's blessings on the minstrel old, and all who list with eager ear!

And up a mount I push a cart; then down the hill it rolling flies.

We'll live in joy and die in peace, and then we'll dwell in Paradise.

|

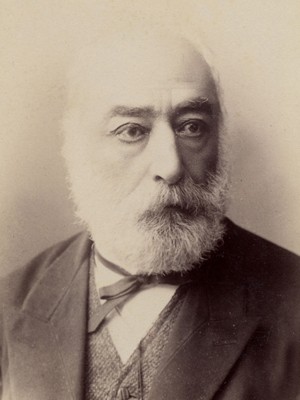

Georgian poet, scholar, and journalist. Raphael Eristavi was descended from the powerful noble family of the Eristavis of Aragvi and studied in gymnasiums in Telavi and Tbilisi before starting his service in the Russian viceroy’s administration. He eventually became a member of the Caucasian Censorship Committee. Eristavi contributed articles on various issues to the journal Kavkaz and played an important role in establishing the Georgian Museum, Georgian theater, and the Society for the Advancement of Learning Among the Georgians. From 1884–1886, he directed the Georgian Drama Society and participated in the scientific study of the text of Shota Rustaveli's Vepkhistkaosani (The Knight in Panther's Skin) poem in 1882. Eristavi’s first major work appeared in 1852 when the journal Tsiskari published his story Oborvanets (in Russian) followed by his first Georgian novelette, Nino, in 1857. In later years, he wrote the poems Ghvino (1868) Tandilas dardi (1882), Beruas chivili, Beruas chafikreba (1883), Aspindzis omi, Tamariani (1887), Dedaena, Neta ras stiri dediko?, Ras erchi mag bichs tataro (1881), Samshoblo khevsurisa (1881) ,and others. Eristavi also tried vaudevilles, and his first play, Mbrunavi stolebi, appeared in 1868 followed by Dedakastma tu gaitsia, tskhra ugheli kharis umdzlavresia (1870), Jer daikhotsnen, mere iqortsines, Suratebi chveni khalkhis tskhovrebidan, and others. Through his journalism and scholarship, Eristavi played an important role in the development of Georgian ethnography and folk studies. He traveled widely all over Georgia and studied in detail the traditions in the mountainous regions of Georgia, especially in Khevsureti, Pshavi, Tusheti, and Svaneti. His works attracted the Russian public by their fluent Russian narrative and the interesting materials which Eristavi retrieved from his travels. Together with Ilia Chavchavadze, he published Glekhuri simgherebi, leksebi da andazebi which compiled folk songs and poems; in 1873, he also published Kartuli sakhalkho poezia on Georgian folk poetry, and four years later, he authored a book on Georgian proverbs and riddles. In the 1870s, Eristavi helped develop Georgian lexicology and technical terminology and produced several dictionaries, including the Latin-Russian-Georgian Plant Dictionary, Georgian-Russian-Latin Language Dictionary, and the first edition of Sulkhan-Saba Orbeliani’s Kartuli Leksikoni (1884). His fiftieth jubilee was a national event celebrated by many poets and public figures. The Land of the Khevsuris Sessia's thoughts |

|

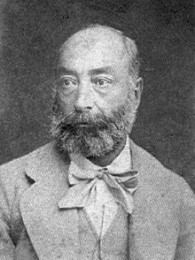

Georgian romantic poet. Related to the Bagrationi royal family, he received an excellent education and began military service in the Russian army in the 1820s. Orbeliani participated in the Russo-Persian and Russo-Turkish Wars, distinguishing himself and quickly advancing through the ranks. In 1832, however, he was implicated in the conspiracy of Georgian nobles seeking the restoration of the Bagrationi dynasty and was exiled for six years. Returning to Georgia, he distinguished himself in the Russian campaigns against Imam Shamil in Chechnya and served as a governor of Avaria and Daghestan. In later years, he attained the rank of general and performed the functions of the governor of Georgia. In the 1880s, he played a leading role in establishing a standard text for Shota Rustaveli’s Vepkhistkaosani (The Knight in Panther's Skin) poem. Orbeliani’s poetry is noteworthy for its patriotism and humanity, and his major works include Iaralis, Mukhambazi and Sadghegrdzelo anu omis shemdeg ghame lkhini Erevnis siakhloves. |

The Knight in the Tiger Skin by Shot'ha Rust'hveli is recognized as one of the greatest works to have been created by human genius. Eight centuries separate us from the author of this immortal epic, but even today its life-affirming passion, shining humanity and heroic spirit, the ideas of patriotism and internationalism that it embodies and the elevated human feelings and moral ideals it expresses link this great literary monument of the distant past with the spiritual world of all freedom-loving peoples.

Rust'hveli's epic has become part of the heritage of all mankind. No less than the people for whom it was written, Europeans and Asians, Americans and Africans can gain from this work something more than a romantic, knightly tale brilliantly told in verse. This is so due above all to the fact that in the past 100 years Rust'hveli's immortal epic has been translated into many world languages.

For centuries Rust'hveli's work, the product of an unknown world and written in a still unstudied tongue, survived only in the native land of the poet, south of the Caucasus mountains in the gorges of the rivers Chorokhi, Rioni, Kura and Alazani.

For world culture the appearance of The Knight in the Tiger Skin was akin to a major archaeological discovery. The Russian public figure, Yevgeny Bolkhovitinov, was the first person of the larger world to take note of this priceless treasure. Writing in 1802, he observed enthusiastically of the poem that “the scenes of action resemble those of Ariosto's poem Orlando Furioso, but the beauty, the originality of the pictures, the naturalness of the ideas and sensations are Ossianic”.

The Knight in the Tiger Skin was written on the eve of the fatal catastrophe which befell Georgia in the “golden age” of its history, when this small but powerful feudal country stood at the height of its political, economic and spiritual renaissance. Scarcely had the book appeared than Georgia was for many centuries torn from the outside world, its once famed culture known only to very few.

Even in the 19th century, although Rust'hveli's epic had been noted and many had tried to bring it, if only in part, to the knowledge of the world, The Knight in the Tiger Skin remained an enigma to the foreign reader. It was only at the turn of the century that the veil concealing the work was drawn aside.

“As Homer is Greece, Dante Italy, Shakespeare England and Calderon and Cervantes Spain, so Rust'hveli is Georgia. ...A people, if it is great, will create song and carry in its bosom a world poet. Such a monarch of the ages, still unknown to Russians, was Georgia's chosen one, Shot'ha Rust'hveli, who in the 12th century gave his motherland its banner and call – ‘Vephistkaosani’- Wearer of the Snow-Leopard's Skin. This is the best poem about love ever written in Europe, a rainbow of love, a fiery bridge linking heaven and earth.”

These words belong to the poet Konstantin Balmont, who translated The Knight in the Tiger Skin into Russian. He recalls his first encounter with Rust'hveli thus: “I first became acquainted with Rust'hveli amid the expanses of the ocean, not far from the Canary Islands, on an English ship bearing the name of Athene, beautiful goddess of wisdom. On board I met Oliver Wardrop, who gave me an English translation of The Snow-Leopard Skin, of which he had a proof copy, to read. The translation had been done with great affection by his sister, Marjory Scott Wardrop. To touch the Georgian rose amid the immensity of the ocean dawns, with the kindly complicity of Sun, Sea, the Stars, friendship and love, of wild water-spouts and fierce storms, produced an impression which I shall never forget. “

Balmont's translation, the first full and truly poetic rendering of the work, began to appear as early as 1916 in magazine instalments.

The English writer Marjory Scott Wardrop visited Georgia in the 1890s. There she met the outstanding Georgian poet and public figure, Illya Chavchavadze, who introduced her to Rust'hveli's poem. Filled with admiration for the work, she threw herself into study of the Georgian language and in 1912 Shot'ha Rust'hveli was brought to English readers in a prose translation. Thus this ancient Georgian poem appeared almost simultanenusly in two world languages.

In discussing The Knight in the Tiger Skin we must inevitably begin by discussing its author. Who was Shot 'ha Rust 'hveli ? Do Georgian historical writings contain any mention of him ?

The earliest references to Georgia and the Georgian people are to be found in Herodotus, “the father of history”. Still earlier, Homer mentions a Georgian tribe, the Khalibi, while writing of the Trojan war. Descriptions of the state of Iberia and ancient Colchis are contained in the writings of Strabo and many Greco-Roman authors.

The age of Rust'hveli was, in world history, the time when the future captains Dzhebe and Subetey were riding and shooting beneath the burning sun of Central Asia, preparing for the wars to come. Bloody clouds were gathering in the incandescent skies of Mongolia; in the West the third crusade was raging and the terrible Saladin, having defeated the knights of Europe, was entering Jerusalem.

Both the political and spiritual future of Georgia and the life of Rust'hveli himself were bound up with these important parallel processes.

But in the meantime, the “Golden Age” reigned in Rust'hveli's homeland. On the throne sat T'hamar (1184-1213), a queen famed for her intelligence and beauty. Her state was united and strong, resting on the firm foundations, which her great forebear, David Aghmashenebeli (the Builder) (1089-1125), had laid. David had taken advantage of the crusades to expel the Arabs and Turks from his country after 300 years of domination.

Georgia's renaissance was closely linked to both Western and Eastern culture. It was at this time that “Iranian literature met the literature of the North, of Europe, that Leili met Isolda, Buddha the legend of Ahasuerus. Georgia was the land, where these two cultural streams, rushing towards each other, met. The focal point of this meeting, a man endowed with a remarkable lyrical gift, intelligence and passion, was Rust'hveli” (Nikolai Tikhouov).

History has no precise facts for us about the great Georgian poet, but The Knight in the Tiger Skin itself and a handful of other historical and literary documents now at our disposal make it possible to form a definite picture of the poet's personality and of the times in which his work of genius was created.

Shot'ha Rust'hveli's life and the time of creation of his poem exactly coincide, according to the events described in it, with the era of Queen T'hamar , down to the dynastic conflicts that reflected contemporary clashes at court.

It is fortunate that the author refers to himself more than once in his poem, introducing himself as Rust'hveli. “I, Rust'hveli, indited a poem. ... Hitherto the tale has been told as a tale; now is it a pearl of measured poesy. “

Of T'hamar the poet writes: “By shedding tears of blood we praise Queen T'hamar, whose praises I, not iIl- chosen, have told forth.” The lines: “I, Rust'hveli, have composed this work by the folly of my art,” and “I am sick of love, and for me there is no cure from anywhere”, clearly indicate the poet's unspoken love for the queen. Some Georgian scholars of Rust'hveli consider that the amatory conflict conveyed in the poem reflects the personal relations of poet and queen and it is possible that isolated coincidences occur, but we lack the corresponding historical and biographical documents to conclusively prove this.

In fact, we possess no precise historical information on Rust'hveli's character. However, the life of Queen T'hamar is presented relatively fully in ancient Georgian historical writings (“Kartlis tskhovreba”) and, in particular, in the stories by “Basil”, the queen's personal historian and court tutor.

Several people bearing the name Shot'ha appear in historical sources of the 12th and 13th centuries and in ancient deeds. Could it be that one of them is the poet ? Georgian scholars have long investigated this question, settling now on one, now on another Shot'ha as the author of The Knight in the Tiger Skin. (It is only since the examination of the Jerusalem fresco depicting Shot'ha that this dispute may, to a certain extent, be considered settled.) Who, then, was Shot 'ha, the poet from Rustavi ?

Two settlements in Georgia have laid claim to the poet. One lies twenty kilometres from Tbilisi, Georgia's capital, and was known throughout for its metallurgical industry. Eight centuries ago this Rustavi was a large administrative, economic and cultural centre in the kingdom of Georgia.

In 1265 the town was utterly destroyed by the Mongols. The builders of modern Rustavi were confronted by a striking sight while clearing a section of the ancient ruins: the headless skeleton of a young girl separated by some metres from her skull. An axe was in the girl's hands. She had evidently been defending herself from an invading Mongol soldier, who beheaded her with his sword. Beside the girl’s skeleton the remains of her devoted dog were found. On that day, 700 years ago, the Mongols also beheaded the town which considers itself the birthplace of Shot'ha Rust'hveli.

The second Rustavi is a small village in the south of Georgia, on the border with Turkey. This part of the country is sometimes referred to as Meskhetia.

The cliff town of Vardzia, which dates from the l2th century, is located here. This cave complex served both religious and secular purposes and had remarkable frescoes depicting Queen T'hamar and members of her family. Here, too, are found the multi-level Van Caves, cut in the l3th century, and the fortress of T'hmogvi, birthplace of Sargis T'hmogveli, author of the Dilarget'hiani, who is mentioned in The Knight in the Tiger Skin. The fortress of Khertvisi and many other historical monuments, which played a major role in the political and cultural life of ancient Georgia are also located here. Meskhetia gave Georgia's culture many outstanding figures, writers, scholars, artists and philosophers. Scholars confirm that the name Shot'ha was particularly common in this province in the 10th, 11th and l2th centuries.

According to tradition Shot'ha Rust'hveli came from this corner of southern Georgia and many scholars now consider that Shot'ha Rust'hveli was a Meskh from Rustavi in Meskhetia. But which of the Shot'has mentioned in historical sources was the poet ? The majority of Georgian literary sources name the author of the poem as Shot'ha, treasurer of the court of Queen T'hamar.

Rust'hveli figures in popular tradition as a minister of the queen. He is supposed to have been educated first in Georgia, at the academies of Gelati or Ikalto, and then in Athens or on Mount Olympus, where many Georgians studied at that time. The poet became a master of Greek, Arabic and Persian and gained an intimate knowledge of the literature and philosophy of these countries before receiving a high post at the court of Queen T'hamar.

Indeed, his poem indicates that Rust'hveli was well read in the ancient philosophers, including Heraclitus and Empedocles; however, many Georgian scholars now assert that the principal source of his ideas was the writings of such Georgian thinkers as Petrus the Iberian, Ioane Laza, Ioane Moskh (Meskh), Yefrem Mtsyre and Ioane Petritsi, who radically revised the ideas of the ancients.

Academician N. Y. Marr consistently advanced the view that Georgians of the 10th and 11th centuries were studying the same problems which were occupying the most advanced minds in Christian countries of West and East during the period and that they were ahead of Europe inasmuch as they were able to respond before anyone else to the new philosophical trends and possessed a model apparatus of philosophical criticism for the time.

According to the same sources and to popular tradition Shot'ha Rust'hveli travelled widely - as is also evident from The Knight in the Tiger Skin - journeying in his old age to Palestine, there in Jerusalem to die. Georgian scholars now have all the necessary documents to prove conclusively that Rust'hveli was minister of finance at the court of Queen T'hamar.

It is known that as early as the 5th century Georgians founded the Monastery of the Cross in Palestine. For twelve hundred years they carried out a great educational and cultural mission from this monastery until it was captured by the Greeks in the 17th century.

There, in the course of the centuries, a history of the monastery was written and information was compiled on its leading figures, the names of whom were inscribed in a “Memorial Book”. Hundreds of volumes in Georgian, Greek and other languages used at that time by Georgians in Palestine, including the “Memorial Book” and the church calendars, passed into the possession of the Greek church and are now kept in the library of the Greek patriarch in Jerusalem.

Georgian scholars have at their disposal only a number of microfilms, among them copies of the church calendars. One of these microfilms states: “On this Monday the funeral mass of the treasurer, Shot'ha, is to take place.” This entry relates to the first quarter of the 13th century .

For many centuries scholars in the poet's homeland knew nothing of this. In the middle of the 18th century the Georgian public figure, Timote Gabashvili, visited Georgian antiquities in Palestine, among them the Monastery of the Cross in Jerusalem. Gabashvili described his travels in a book entitled A Journey, in which the following reference to the Monastery of the Cross occurs:

“Below the cupola the columns have been renovated and painted . . . by the treasurer, Shot'ha Rust'hveli, who is himself depicted there as an old man.” Gabashvili conjectured that Shot'ha the treasurer must have been the poet, Shot'ha Rust'hveli. He based his supposition that Rust'hveli was a minister of finance on the traditional legends of the people.

Who destroyed the cupola and columns of the monastery, restored and painted with the assistance of Shot'ha Rust'hveli, and when did this happen ?

The Monastery of the Cross was destroyed and rebuilt, repaired and reconstructed several times in the course of its history. It may be assumed that Shot'ha Rust'hveli arrived in Palestine after the destruction and capture of Jerusalem by the Egyptian sultan, Saladin, during the third crusade. Georgian scholars possess a document written by the Arab historian, Ibn-Sheded, which states that when in 1187 Saladin took Jerusalem, the Monastery of the Cross also fell to him. Queen T'hamar of Georgia offered a ransom of 200,000 dinars for the cloister. Some researchers speculate that the queen sent her minister of finance to Jerusalem on this mission.

Rust'hveli took part in restoring the walls and columns of the Georgian cloister in Palestine, which had been destroyed by Saladin. As a mark of gratitude, Shot'ha himself was depicted on one of the columns of the monastery. Rust'hveli was portrayed in secular dress, kneeling beside St. John Damascene, the great medieval Christian poet, and Maxim the Confessor, who developed Christian philosophy and theology on the basis of neo-Platonism. Of interest here is the fact that in the 7th century Maxim the Confessor opened up the way to the teachings of Dionysius the Areopagite, who was considered a neo-Platonist in the Middle Ages, although he was an orthodox Christian. Dionysius is referred to in The Knight in the Tiger Skin as “Dionos”; his thinking is entirely Christian and philosophical and, Georgian scholars assert, it is this view of the world that was the source of Rust'hveli's poem. The poet may have personally chosen a place for this fresco between these two saints.

All these facts have become known only in recent years, since Georgian scholars obtained a portrait of Shot'ha from Palestine, for the fresco of Rust'hveli about which Timote Gabashvili wrote in the mid-18th century and which was described by the members of a scientific expedition in the 19th century disappeared at the end of the last century. Georgian scholars arriving in Palestine failed to find it. How many secrets were buried together with the portrait! Indeed, everything that has been written above has come to light only since the rediscovery of the fresco. Georgian travellers to Palestine at the turn of the century sadly reported that the whereabouts of the portrait were unknown. The fresco seemed, indeed, to have been irrevocably lost.

This problem began to concern me fifteen years ago, when the idea was conceived of celebrating Rust'hveli's jubilee. I resolved to get to the bottom of the mystery surrounding the Rust'hveli portrait in Palestine.

Our expedition, which consisted of Akaky Shanidze and Georgy Tsereteli, both members of the Georgian Academy of Sciences, and myself, arrived in Palestine in the autumn of 1959. I have described the scholarly work performed by the expedition in detail in Palestinian Diary and interested readers may refer to this. I shall confine myself here to noting that after careful investigation we succeeded in discovering the Rust'hveli portrait which, fortunately, had been neither erased nor damaged, but was hidden beneath a thick layer of black paint. From the 17th century on, Greek church figures had systematically resorted to actions of this kind to wipe out every distinctively “national” trace from the old Georgian monastery. We cleaned this fresco, which bears the inscription “Rust'hveli”, and brought a copy of it back to Georgia. The Palestine fresco is the most valuable biographical document bearing on the great Georgian poet and thinker that we possess today. The portrait and the J erusalem church calendar helped to conclusively prove that the poet Shot'ha Rust'hveli and the treasurer Shot'ha mentioned in Georgian historical sources and popular legends are one and the same person.

The original of The Knight in the Tiger Skin has been lost. It may have been reduced to ashes in 1225, when the ferocious Djalal-ad-Din put Tbilisi to the torch, or later, when the Mongols burned Christian manuscripts in the squares of the city. It could have been torn to shreds during raids by Persians and Turks. During that dark period much was destroyed and lost in Georgia.

“Mose Khoneli praised Amiran, son of Daredjan; Shavt'heli, whose poem they admired, praised Abdul-Mesia; Sargis T'hmogveli, the unwearying-tongued praised Dilarget'h,” Rust'hveli tells his readers. Where are the Abdul-Mesia, the Dilarget'hiani and many other works now? They have been swallowed up by the black waves of history. Even today we cannot find these literary monuments and traces of them survive only in folklore, in the form of separate fragments, like magnificent ruins of the architectural monuments which are scattered the length of Georgia. It is a cause for great joy that The Knight in the Tiger Skin passed through flame intact.

The most ancient manuscript of Rust'hveli's immortal work extant dates from 1646. A number of earlier records have been preserved in the form of fragments, dating from the 15th century .One such fragment, consisting of only a few lines, was discovered recently during the comprehensive excavation and study of the Van Caves. An inscription by the hand of poetess Anna Rcheulishvili was found on a rock. She refers to her sufferings in words from The Knight in the Tiger Skin: “I am sitting in a castle so lofty that eyes can scarce see the ground.”

As a result of assiduous research work more than 150 manuscripts of The Knight in the Tiger Skin have been discovered and these are now kept in Soviet libraries. But not all these manuscripts are suitable for scholarly purposes.

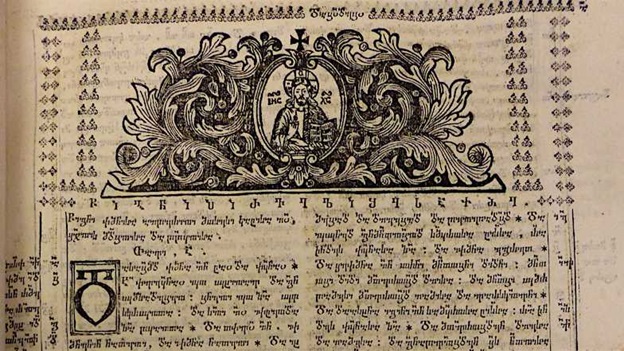

The Knight in the Tiger Skin was first published in 1712 at the initiative and under the editorship of King Vakhtang, founder of the Georgian printing press. Vakhtang had apparently studied ancient manuscripts of the poem, of which far more existed in his time than now and which evidently dated from earlier period. On the basis of these manuscripts he produced a scholarly edition of the poem.

In the absence of the original the text of The Knight in the Tiger Skin underwent constant changes at the hands of copyists over the centuries. Many “embellishers” inserted new passages into the poem at will or in accordance with the wishes of those who ordered copies from them. In the 16th century a revival began in Georgian culture and literature and the popularity and influence of The Knight in Tiger Skin grew immeasurably. Copyists of the poem made various changes to the plot, while interpolators were revising the poem to bring it ideologically into line with the teachings of the Christian religion. For these reasons the primary text of the poem is distorted in many manuscripts. In subsequent centuries the poem was increasingly “enriched”. The first editor of Rust'hveli's epic had much to do in order to remove obvious insertions from the text and “turn obscurity into clarity”.

Illya Chavchavadze, prominent Georgian writer and public figure of the 19th century, did a great deal to discover the genuine text of the poem. However, even today the process of restoring the text to its definitive form is still continuing. The Georgian people bore its beloved work- The Knight in the Tiger Skin- through the flames of the ages, like “a Banner and a Call”, whose creator, “conducting his lover heroes through all kinds of trials, made them shine in life with such glory that they could never die. Herein lies the advantage of the Georgian genius over his European contemporaries and later poets, just as the Indian, Kalidasa, stands above geniuses of the drama thanks to his Sakuntafa. Here, after all, there is no devilish enchantment of death, but a full harmony of happiness, higher and more perfect than of Europe's geniuses. ..” (Konstantin Balmont). The people felt the spirit and philosophical essence of the poem-felt it and recognised in it the most precious contribution to its spiritual treasure-house. Generations of Georgians have worked and defended their land under this banner and in response to this call : “What is worse than a man in the fight with a frowning face, shirking, affrighted and thinking of death ? In what is a cowardly man better than a woman weaving a web! It is better to get glory than all goods !”

It is characteristic that people were and still are to be found in the inaccessible mountains of Georgia who know all 1,500 verses of Rust'hveli's poem by heart. Worthy of note, too, is the fact that for many centuries The Knight in the Tiger Skin was considered a bride's most valuable dowry. Every Georgian kept a copy of the poem beside his bed, together with the Gospels. Foreign travellers even considered that Georgians had two gods-Christ and Rust'hveli. The priests could not forgive the poet for this and in the centuries to come persecution began of the man whose portrait had, in his lifetime, adorned Christianity's most holy place-the Monastery of the Cross in Jerusalem. According to some sources, in the 18th century almost the entire first edition of his poem was thrown into the Kura River by clerics.

That the love story contained in the poem unfolds in Moslem rather than Christian countries, principally in Arabia and India, was also not to the liking of churchmen. But whatever the forces opposed to it, The Knight in the Tiger Skin survived triumphantly through the centuries and is as popular today as it has ever been.

Rust 'hveli considered love the principal sign of human nature and humanity. His immortal poem is a hymn of love and its dominant note, struck by Rust'hveli with characteristic brevity and philosophical profundity, is the eternal truth that “only love exalts us”.

Let us turn our gaze to the cherished pages of The Knight in the Tiger Skin. But first we must clarify, if only in the most general terms, the soil from which the poem sprang, the spiritual atmosphere in which it flowered. Humanistic ideals and aspirations pervaded Georgia's culture in the age of Rust'hveli. Indeed, if one takes in the whole sweep of the period, one might form the impression that the forces creating Georgian culture before Rust'hveli had, as it were, hastened to erect the walls of this magnificent building so that the poet could crown it with a splendid dome, only a few decades before the fatal catastrophe that broke over his land.

The cultural advance in Georgia was remarkable for the pace of its development, its richness and creative tension. Following the adoption of Christianity, Georgia succeeded in creating more in the period between the 4th and the l2th centuries, amid unending defensive wars and under the constant threat of destruction, than could have been conceived of in so short a span of time. “During my trips to Georgia I saw the monuments of Georgian architecture, frescoes, etc.,” Alexei Tolstoy wrote. “I must say that when I met with these treasures of the 1Oth and 11th centuries I was convinced that Georgia had created all the prerequisites for the Renaissance and had produced works equal to those of Giotto two centuries before Giotto.”

The entire life of the Georgian people was filled with tireless seekings in the field of culture, and especially in that of belles-lettres. In the very first hagiographical works and soon thereafter in religious poetry and historical and philosophical writings as well, clear signs of an interest in man, in his total spiritual and physical being, emerged. Delight in man's beauty, love, which elevates him, and his search for truth began to come thematically to the fore.

Profound knowledge of the works of Aristotle and Plato revealed by Georgian literature of the time was not fortuitous; nor was the emergence in the 5th century, at the heart of religious literature, of highly developed belles-lettres, written in a rich literary language. Georgian culture in the 12th century was distinguished by particular variety and richness. The kingdom's two academies - Gelati and Ikalto -offered their students a general education while also serving as major centres of science and philosophy.

Moreover, as I have already noted, a lofty synthesis of Western and Eastern culture was brought about in Georgia by virtue of its geographical position. All this formed the foundation and walls of the magnificent edifice which would have remained incomplete had not Georgia produced Rust'hveli.

Rust'hveli accomplished and expressed with great power that elevated human ideal of which the medieval world-the medieval world alone could only dream. He raised man to heights inaccessible to his own and subsequent times.

The Gordian knot which medieval thinking, whether religious, philosophical or artistic, was unable to unravel is known to all. This was the gulf that had formed in knowledge between God and the real world, between creator and created. The best minds of the Middle Ages laboured in vain to find the solution to this mystery, but their conclusion was always the same: the deity alone is real, while the created world is only an appearance, an abode of evil and the possession of Satan. Mankind gazed with fascination into this chasm and at the two shores of the gulf without finding a way out of the problem. If philosophers were able to glean hope from a rejection of earthly things, placing their trust solely in “the other shore”, the fate of artists and poets was far more complex and difficult, for the very nature of their work placed them in the here and now, on the earthly shore, while the message conveyed by religion and philosophy was that only the life of the other world was real and everything earthly was worthy only of rejection and condemnation.

This sense of being in a hopeless spiritual dead-end left a deep and sombre mark on the work of medieval artists.

This, then, was the spiritual atmosphere of the age of which Rust'hveli was a witness. One preliminary observation should be made. Let us imagine for a moment that we know nothing of Rust'hveli's view of the world and that we have not studied his poem from this point. Nevertheless, it will be clear to everyone who has read it, even once, that the poet who emerges from its pages could not, simply in terms of his psychological cast of mind and spiritual make-up, have been an adherent of a dualistic concept of life.

A world dislocated and divided was inconceivable to the author of The Knight in the Tiger Skin, just as heroes with divided souls or split natures were inconceivable to him. The characters of The Knight in the Tiger Skin are monolithic, whole, carved, as it were, from huge single blocks of stone. Even when Tariel has lost hope in meeting his beloved, despairs and is on the verge of madness, in flight from life and alone in the desert, he does not cease to be a whole person, for in the situation that has emerged and the circumstances fate has presented him with he cannot act, think or suffer other than as a whole person.

It is clear from what has been noted above that Rust'hveli's position is that of a monist. But what is the nature of this monism ? Can we suppose that Rust'hveli overcame the dualism of his age simply by dismissing the question of the other world and of the very existence of “the other shore” ? This point of view has been expressed by some Georgian scholars, who claim that Rust'hveli was absorbed by this world alone and that the sphere of his interests did not essentially extend beyond the bounds of the earthly.

I believe that thus posing and resolving the question means its over-simplification. The historical approach to this complex issue should not be neglected: there is little profit to be gained from ascribing to a 12th-century poet conclusions of which mankind became firmly convinced only in the course of the last century.

Free, unfettered thought should not be confused with the atheistic and materialistic thought. These domains were quite out of the question in the 12th century. Complex cultural phenomena and philosophical ideas must be explained on the basis of the laws inherent in them and not in terms of laws imposed on them from outside, even if this is done from the most advanced modern point of view and with the best of intentions.

No, Rust'hveli, contrary to the conclusions drawn centuries later by human minds, certainly did not dismiss the question of “the other shore” ; but, despite the dominant tradition of his age, neither did he turn away from the reality of “this shore”, even in theory. Rust'hveli was able to overcome the apparent contradiction, to bridge the gulf. How ?

The gulf was conquered by declaring it - and not the created world - to be an evil, which, in Rust'hveli's concept, was illusory. The gulf dividing creator and creation was only apparent. Anyone who wanted to enter into communion with God must demonstrate the illusoriness of the gulf, that separates man from his creator, by conquering Evil. Only active struggle against evil would give an opportunity for communion with the Almighty.

The world was not created by God for it to be made an abode of evil. The earth, adorned with incomparable and varied beauty, was created for people, since man himself was involved in God and was a part of him, created by him. Without man the unity and harmony of the world was inconceivable. According to Rust'hveli's concept of things, love, even in this world, could bring man into contact with the supreme harmony and thereby make him closer to the divine.

Man was given intelligence in order that he might know the world created for him and make his knowledge an instrument for achieving the supreme goal. For the truly wise man there was no gulf separating heaven and earth: he knew it was the gulf, not the world that was illusory. Apparently essential evil was only the product of ignorance and was overcome by active knowledge, which must not remain “wisdom for its own sake”, but which must be wholly directed towards the affirmation of good, towards the supreme goal of communion with God, towards the highest order and harmony.

It is here that the fundamental difference between Rust'hveli's view of the world and traditional medieval thinking lies. Rust'hveli considered that the world was created by God for man and that man himself was a part of God. It was therefore for man to live, create and act and not to reside in a prison of evil. The world was illuminated by the sun and the sun was the visible image of the creator. The source of all earthly light was God himself.The poet was convinced that one must love a real, living being, not a lifeless symbol of God. Love brought us into contact with the supreme harmony, since it was through love that evil was conquered, the fetters broken and the illusion that creator and man are divided dispelled.

Rust'hveli knew that in order to grasp the supreme truth man should not await heavenly enlightenment in a mystical ecstasy. The creator had endowed man with intelligence with the object of embodying in him His own nature. God and man were united by virtue of intelligence and it was for this very reason that the possibilities of human intelligence were limitless.

There was certainly no need for Rust'hveli to go beyond the bounds of Christian teaching for confirmation of his philosophical ethical ideas. If it was true that the objective seeker after truth could find every one of these principles in religious dogma, how much more so was it the case that they could be grasped by the intuition and wisdom of a poetic genius. It is also by no means impossible that Rust'hveli saw and perceived immeasurably more in Christian ideas than was accessible to ecclesiastical commentators. Of course, none of these truths would have been stamped on the poet's consciousness with such clarity and harmony had he lacked the philosophical experience of Pseudo-Dionysius the Areopagite.

Once the gulf dividing creator and created had been overcome and the forces directly raising man to divine perfection revealed (love and wisdom), it inevitably became clear that man's activity had value for existence, both divine and earthly. Hence the vital conclusion that the earthly activity of man as he strives to commune with God is by no means all vanity and confusion in a world of vanity (as was claimed in the theories of the Middle Ages), but an integral part of an inconvertible process of development and movement in an indivisible universe. Ultimately this earthly human activity was contiguous with divine action. But, of course, only that cause which is directed by the active personality, filled with love and wisdom, to the supreme goal, to the divine ideal can itself be divine. Existence un-illuminated by the light of love and intelligence is doomed to stagnation and torment in the prison of evil, where everything is short-lived, illusory and transitory, barren and impotent. There all the laws of earthly life as a whole operate with implacable severity, but in a fog of lovelessness and non-under- standing, since, as we know, according to Rust'hveli's most important philosophical and ethical conclusion, “evil is in this world for a moment, goodness is immutable ,”

This is why, when we say that Rust'hveli raised man to inaccessible heights, we have in mind the idea of humanity and not simply of one man. Tariel and Avt’handil, Nestan and T'hinat'hin and their friends, too, are a living embodiment of this idea. They are truly pinnacles of creation, lords of nature, monarchs of the spirit.

Therein lies the explanation for the constant comparisons between the heroes of the poem and the sun and their frequent personification by the image of the sun. In turning to a general artistic characterisation of the poem, we should direct our attention to a particular circumstance. While the structure of The Knight in the Tiger Skin is extremely complex, being conceived and worked out on several levels, each of these levels is characteristically elaborated with the same thoroughness and consistency. The various levels interpenetrate each other and only by the most painstaking analysis can they be separated.

I believe that in all literature only the smallest handful of works are as perfectly constructed as Rust'hveli's poem. But even more important is that the poem, as conceived and created, presupposes an unusually wide audience. The Knight in the Tiger Skin has always been equally near and dear to the learned scholar and the humble toiler. Both find in the poem words addressed to them, comprehensible to them and dear to them. And each perceives its idea, which today shines with a special light at us, its millions of readers. This idea is simple and great. Rust'hveli reminds us, contemporary men and women, that man and man alone is the greatest value in the world and that he must be fine and perfectly harmonious. His body and soul, his mind, feelings and actions must be fine. It is man's appointed role and hence his obligation to develop within himself such a will that his thoughts and actions are directed towards good and towards noble ends only.

But Rust'hveli also warns us that for man to be truly great, for him to be elevated to heights which are worthy of him, a contemplative and passive humanism, no matter how noble or well-intentioned, is not enough. For “the road to hell is paved with good intentions”. Only activity-and heroic, self-sacrificing activity, if necessary-eternal, unflinching and tireless action can trample evil underfoot and ensure the triumph of good. “Evil is killed by good, there is no limit to good “' This is what makes a man a man and ensures the triumph of a world order in which true harmony reigns.

To liberate Nestan-Daderjan from captivity, incredible trials had to be undergone, intolerable torments endured, insurmountable obstacles overcome and more than human feats, almost inconceivable for ordinary mortals, carried out. This reflects Rust'hveli's moral maximalism: the poet never abased his heroes with petty tasks, difficulties and obstacles. But even if we leave aside the symbolism contained in the story of Nestan's capture and liberation and read Rust'hveli's poem from a purely modern point of view, in terms of what interests us most, the same wisdom that underlies every level of this sophisticated poem will unfold before us: evil can be subdued only by the active force of triumphant good and good can reign on earth only in irreconcilable and victorious conflict with evil.

This is why The Knight in the Tiger Skin has become a priceless treasure of the people, why this poem has constantly awakened and sustained man's faith in his own powers and in the triumph of good.