| Thy dreams, dear mother, will become A garden full of happiness. O weep not so, nor drown thy heart In languor of grief's heaviness. Our wounds are healed, and once again, We're ready for a dubious fight. The morn we'll greet with battle cries, With deeds of wonder and of might. Tamari's sons will flood the skies With radiance of vict'ry's light, And with our lives we'll guard and keep The torch of honour ever bright. For glory born of fallen pride We ne'er will barter Georgia's right! We'll fell the enemy or die, And ne'er like cowards shirk a fight. Though now we're far from Georgia, yet, Our hearts for her with longing sigh. One thing sends fires through our veins, As wondering we see on high, Above a red-fanged field of war, Upon a flying steed — a knight! He holds a flaming sword that like A star of hope shines in the night! His glowing eyes flash sombre light. And there midst man-wrought hell and woe That knight protects our souls from blight! When all is still and not a sound Is heard of cannon's deafening roar, When battle's surging din is hushed, And thoughts invade my mind once more, I seem to see thee, mother, combing Wool in the quiet of the night. Thy head is bent and tears like torrents Fall on the carded wool so white. A homespun 'chokha' wilt thou sew For me, made holy by thy tear; No sword can tear it, nor can fire Burn through the cloth, O mother dear. And through the long and dreary night Sleep toucheth not thy tearful eyes. God grant to happy smiles and song Be changed thy mournful dirge and sighs. Farewell! the battle-trumpet rings, And bids us rush where soldiers' cries Resound; where blades like lightning blaze And cannon's volley rends the skies. But woe! if glory's thrill is o'er And all our hopes turn to despair! Woe if the spark of valour's flame To ashes cold be quenched fore'er! Perchance the raven black will croak A dirge of doom o'er Georgia fair! Farewell! the battle-trumpet rings And bids us rush where soldiers' cries Resound, where blades like lightning blaze And cannon's volley rends the skies. Farewell! and weep not, for thy son Will fell the foe or bravely die! |

|

|

(An assembled group of Khevsuris are amusing themselves by drinking and singing in honour of warriors whose deeds have made the world wonder. They sing songs of praise to the accompaniment of softly humming panduris. Sitting with them is a pale-faced, grave and dignified figure. Strange tales are told of Mindia's past) For twelve years Mindia was held A captive by the Kajis fierce. Estranged from home, from friends and kin, He spent his dreary days in tears. Thus moments, hours, weeks and months Through tedious seasons led him on, Tied to a rope of misery From blasted hopes and evils spun. Thoughts of his distant native land Like balm flowed o'er his maddened brain. He shut his eyes, and lo! there glowed The land of Khevsuri again. Dim visions of her snow-capped mounts, Her winding paths and murm'ring streams, His parents, kin and cherished friends Invaded all his thoughts and dreams. His lowly hut now seemed to him A paradise beneath the skies... And as he thought and pined for home Sobs burst from him, tears filled his eyes. With time he lost all faith and hope Of ever seeing home again, And longed to find relief in death From all his miseries and pain. ….. Once o'er a blazing fire he saw A cauldron full of serpent's meat. It was the Kajis' choicest dish Which they with relish oft would eat. Now Mindia believed if he Ate of the loathsome meat, 'twould turn To poison in his veins and every Fibre of his body burn. He ate one piece, and sickness smote His every nerve: a chilling sweat Ran down his face, and he could scarce Repress the horror that he felt. But suddenly it seemed to him That from above flowed splendent light And spreading through his veins he felt A surging stream of strange delight. New wisdom pierced his wond'ring brain; He saw the world with different eyes, He saw it smile, he heard it speak, He knew the meaning of its sighs. All things that breathed or lived had tongue, Held converse soft in language strange; And as he learned their secret thoughts He wondered much at all this change. Though Mindia's now sharpened eyes In deepest hell and darkness crept, Though earth and sky and forest, mount, Communed with him or silent wept, No wickedness or evil thought Entered his noble heart or brain. Thus skilled in Kajis' mystic art He strove to banish every pain. All feared his superhuman powers, His God-like strength and piercing eyes. The Kajis fumed and burst with rage To see the mortal rendered wise Inspired, full of life and courage, No more did Mindia despair. He cherished now the hope of breaking The chains of slavery fore'er. ….. Soon Mindia became renowned In Pshav-Khevsuri; and his fame "With time increased, and far and wide Was spread the glory of his name. Th'illustrious Queen Tamari smiled In pride and blessed him from on high And said: "Though strong the enemy, His might will Mindia defy, And naught can crush Pshav-Khevsuri As long as Mindia is alive, For with his powers he'll overcome The foe however hard it strive." He snatched from gaping jaws of death The wounded, sore, nigh cleft in twain, Restored to health the dire diseased, Relieved all suffering and pain. And Pshav-Khevsuri's soldiers brave Stood ever ready for a fight. Thus all praised Mindia the grave, His wisdom and his deeds of might. ….. 'Twas early spring. The world awoke From hoary winter's sleep profound, In fields the flow'rs breathed fragrant balm, The hills with verdure fresh were crowned. The scented buds with bursting smiles Peeped forth through emerald and dew. And Mindia with throbbing heart Roamed mount and vale 'neath heavens blue. He loved to be with trees and flowers, With twitt'ring birds and butterflies; And nature, lovely as a bride, Saluted him with joyous cries. The flowers blushed like virgin maids As each its heart to him unveiled, The trees and grass with rustling swayed, And Mindia with gladness hailed. He saw them tremble as they heard The fondling breezes whisp'ring love, And hearkened to the birds as they Disburdened their full souls above. He knew the longings of their hearts, Their troubles, dreams and all their fears; Their wish to bring relief to man Made Mindia shed happy tears. He learned what root and herb distilled, A soothing balm, for grass and flowers Begged him to pluck them, and thus heal "Wounds by the magic of their powers. The songs of birds were more to him Than melody or sweetest sound; It was the language of their hearts That in his soul a refuge found, Oft Mindia, with axe in hand, Went to the forest for some wood, But as lie raised his axe, a voice Broke through the forest's solitude. In cries that shook the frightened leaves He heard the pleadings of the tree? It brought deep anguish to his heart And made him suffer bitterly. "Thou hast an axe, and strong thou art! Why strike me down and kill me so!" Strength ebbed from him, his slack hand fell, The axe dropped on the ground below. He stood bewildered as the trees All wept and pleaded for their lives. Their tears seemed drops of blood to him, Their sighs cut through his soul like knives. Thus Mindia went slowly home, Unhappy and with troubled heart. He bent before the fireside low And raked the dying embers lest The fire extinguish and expire, Then brought some twigs and heaps of hay To feed the flick'ring feeble fire. He called together all the folk. "The trees feel joy and pain," said he, "Cut them not down! Use only twigs And straw for fire, I beg of ye." In this all thought him queer, for they Said: "God has made all things to be A blessing for the mortal man." None hearkened to him, and the tree Was cut. And to this very day Man fells the tree and thanks the Lord. ….. (It was a holiday, and the Khevsuris were gathered together. They praised Mindia's wonderful powers. But Chalkhia, wished to prove to them that Mindia was an impostor and only pretended to be superhuman. He said that Mindia differed in nothing from them; that the plants and animals were created by God for man's use, and Mindia's talk was all nonsense. Many agreed with Chalkhia. Mindia, who was sitting in their midst, paid no attention to those about him. Tears were in his eyes; no one could understand why. When asked the reason for his tears he pointed to two birds that were perched on the branch of a tree near by. One of the birds, he said, was telling the other of the death of their little nestlings. The mother-bird was weeping. And as the Khevsuris looked up, the bird suddenly dropped down on the ground before them dead with a broken heart. All were astounded, and those who had doubted Mindia's powers now believed in him the more. But nevertheless, they continued to hunt and cut down trees. The enemy invaded the country many times, but thanks to Mindia victory was always on the side of the Khevsuris. In the meantime Mindia had married. He was obliged to hunt and cut down trees in order to feed and keep his wife and children warm. And here began the tragedy of Mindia's life. He felt, as he continued in the ways of man, that lie was gradually losing his wonderful powers. Nature soon spoke to him no more. It was early morning. From Mindia's hut could be heard the voices of Mindia and his wife Mzia. He was blaming her for all the misfortunes of his life, and in bitter words expressed his regret at having married her. Mzia reminded him of how he had wooed and loved her. She tried in vain to make him see that she and her children were not the cause of his suffering. He then confessed that he had lost his magic powers and expressed his fear for the welfare of his country.) The world was wrapt in flimsy veil As from the sky poured sheeted rain; Down mountain sides the waters sped And serpent-like flowed on the plain. The leaves received in patters soft The hissing rainfall from the sky. Each flower beneath the raindrops shone Like Queen Tamari's sparkling eye. The sheep like gems adorned the hills, Sweet-scented was the air and bright; And hearts rejoiced as nature poured Abundant beauty and delight. Fair is the world, yet troubles kill All joy within the human breast. Countless the wretched, but man knows But few, and cannot see the rest. Dark forms of hurrying men were seen, From far resounded shouts and cries: "Where is our leader? Seek him, quick! Find Mindia, the ever wise! The bridge, o'er Arghun is destroyed By the advancing enemy. We must with courage beat them back, From Scythians our country free!" Khevsuris thronged upon the field Made ready for the coming fight. In every breast there burned a flame — Lore for their country's honour bright. Now after many years of peace The foe, athirst for combat new, Had once again besieged the land And Khevsuris in tumult threw. The Pshav-Khevsuris ready stood Awaiting for the morning light. Shields, swords and falchions like a sea Of flashing silver lit the night. Each knew that if the leader of The Scythians were captive made, 'Twould free the country and the world Of one who like a threatening blade Was harbinger of tears and woe. The hero's name in every heart Would like a torch forever glow. Brave women with their children went To towers where they in haste prepared Some food and wine in sheep-skin sacks With anxious hearts and loving care. ….. Twilight its mantle gray spread o'er The valley, field and mountain high, Flow'rs drooped in prayer as evening strewed Her purple shadows from the sky. Aragvi hummed in solitude, The landscape faded from the sight, Loud voices rent the twilight's gloom And broke the stillness of the night. "Pshav-Khevsuris, unsheathe your swords! Crush down th'usurping enemy! Your threatened country needs you now, Fight valiantly for victory!" 'Twas dark. No shepherd's whistling clear Was heard to cheer the gloomy night. Dark forms were seen, and things of worth Were hid away from human sight. The sheep were led to safety, then The folk to shelt'ring forts retired. All wait impatient for the dawn With faces set and hearts afire. ….. On Khakhmat's sacred altar gleamed A candle's quiv'ring feeble light, Its yellow rays embraced the trees, Expiring there in sheer delight. At times the light gleamed brighter still And flung the shadows black aside, Then, like a soul in agony Of death, it flickered low and died. Enough remained of sombre light To see two figures on the plain; One held a blood-stained sword, and on The ground there lay a bullock slain. Berdia "God's blessings on thee, Mindia, Upon thy faith and sacrifice, May He thy ardent prayers receive And hearken to thy endless sighs. Thou art the comfort of our lives, The Pshav-Khevsuris' faith and pride. Heaven and earth extol thy name With hymns that echo far and wide. I wonder much, my Mindia. To see thee here both night and day. What troubles thee, what hast thou done Thus ceaselessly to weep and pray? To God we owe immortal thanks, His praise resounds beyond the skies; May He forgive me, but thy ways Exceed all bounds of sacrifice!" Mindia "A bullock, ox, three cows have I As offerings to our Lord on high; Perhaps He'll hearken to my prayers And heal the wounds that make me cry." Berdia "What wounds, my man, can trouble thee, What pain concealed makes thee despair? Thou hast the power to cure all ills With magic herbs and cordials rare." Mindia "My tongue is tied, no words can ever Express why I thus anguished groan. 'Tis easier to speak of troubles Endured by others than one's own. Does he who gold and silver hoards Open his purse for all to see? O woe! Pshav-Klievsuri is doomed, Condemned by destiny's decree." Berdia ''Thou art our pride, our only hope, The idol of Khevsuri's heart. Thou art the favoured son of God, Schooled in the powers of magic art. When man by illness is oppressed, And sorrow wrings his tortured soul, Thy wisdom banishes his woe, Thy powers restore him, make him whole." (Mindia knelt before the altar and with upraised hands pleaded to God to heed his prayers and bring him back to grace again.) ….. Down poured the rain in hissing sheets, The skies frowned o'er the darkened world, The rumbling sound of loosened rocks Was from the depth of midnight hurled. The thunder pealed, then rumbled on, The high winds howled as if in pain, The grass and flowers drooped low in fright, And shuddered 'neath the trampling rain. On Khakhmat's rock no more was seen The feeble gleam of candle-light. No more did they who weeping prayed Kneel there that awe-inspiring night. The sacred altar stood unmoved As winged fire in the heavens flashed. Below the haughty Aragvi Upon the cliff in fury dashed. ….. (Women were seen in a tower praying for the welfare, of their country and their men. Mindia's wife, Mzia, was also there. She looked troubled. She confided to Sandua (a Khevsuri woman) how Mindia had changed of late. She told her of a dream she had had): "I saw a vision in my sleep So turbulent and full of dread, That ill-forebodings fill my mind And o'er my heart their poison spread. A furious storm raged o'er the land, Black clouds drew down the weeping sky, The lightning leaped from peak to peak, And deaf'ning thunder rolled on high. I almost screamed in fear to hear Such groans of driving wind and rain, To see such bursts of blinding fire, Such tumult wild and hurricane. Confusion swelled; the sky and vale All seemed to mingle in a maze Uniting hell with earth's despair. But suddenly in lightning's blaze The mountain shook and overturned; The shattered trees and rocks were whirled Convulsively into the air, Then into chasms dark were hurled. A fiercer blast the valley shook, Cataracts from the skies descended; Upon the plain, with sullen roar, The waters swelled and upwards tended. A horrid noise was heard above A roar that rent the stifling air, Lamentings wild in dread of death And anguished cries of great despair. Shields, swords and corpses floated on The surging waters of the flood; And none there was to weep and mourn Over the dead with tears of blood. The house from where I saw this hell Stood safe upon a rocky place, But soon the waters curled, and lo! The cliff was shattered at its base And in one mass of wreck was swept Away upon the rushing tide. I screamed in terror as I felt Myself into the waters slide. Thus caught in Satan's frenzied whirl I rent the air with cries for aid; Pressing my children to my breast "With bursting sobs to God I prayed. I tried to clutch the shore, but woe, It spurned my clinging, trembling hand! Then o'er the faces of my babes I flung a veil to hide the land Where features black and blood-shot eyes Of doom-wrought men I saw with fright. Into the wild insurgent stream They pushed me back with all their might. "Tis doom to land upon this shore! God's will be done!' they loudly cried, 'Go swiftly back before 'tis late, And follow thou the rushing tide!' Just then before me I beheld Mindia on the waters fleet. He turned to me and sadly smiled; Then spoke in accents low and sweet: 'Forgive me if I wronged thee with My bitter words, beloved mine. Thou seest the Wheel of Fortune turn, Yet do not weep for me nor pine. Tend well our children, shield them from Life's bitterness and misery.' Ah me! that dream forebodeth ill. Fear makes me writhe in agony." (The Khevsuris were ready for the coming fight. They wished Mindia to lead them and did not believe him when he told them that he had lost his powers. They vowed that without his leadership they would not fight. He yielded. The place he chose for battle gave rise to apprehension and fear, but having sworn they had no way but to obey.) Two days and nights beyond the mount The battle raged in deadly swell. Tigers with lions fiercely strove In gaping jaws of roaring hell. As gleams of steel flew dazzling o'er The struggling mass upon the field, Heart-rending groans and cries were heard Above the clash of lance and shield. Who will to death his glory yield? Who'll breathe his last upon that plain? Who'll find renown and victory there, And freedom for his land regain? Five Khevsuris with faces grim Stole from the field without a sound. They bore a burden o'er the mount And laid it gently on the ground. It was a wounded warrior, A Khevsuri whose bleeding head Was with a kabalakhi bound, And o'er whose face death's pallor spread. The Khevsuris "Why rush into the jaws of death, And like a madman fight in vain? The truly wise and prudent chief Should for his land his life retain; For who can tell, the odds may turn, And we may drive them back again." They turned and rushed beyond the mount With waving swords and hearts aflame, Athirst for triumph o'er the foe With deeds that claim immortal fame. 'Tis agony to yield to death One's vital breath and God-like clay, Yet better feel the pangs of death Than one's own country to betray. Let cowards hide their trembling frames Beneath a woman's dress of shame; But he who braves the foe will live Immortal on the page of fame. Meanwhile Mindia gnashed his teeth As he lay there beneath the skies, For disappointment and despair Burst forth in smothered groans and cries. He struggled long to free his hands From bonds that cut into his flesh. He longed for death upon the field Of battle, not within this mesh. When Mindia unloosed his hands And staggered to his feet again, Fire raged in every wound of his And made him wince with awful pain. A sudden terror froze his blood, He scarce believed his staring eyes, For he beheld the village glow In blazing flames that lit the skies. Aghast was he to see this sight. Cold sweat in drops o'erspread his brow. Hope died within his inmost heart, And crushed he wavered 'neath the blow. His stony eyes were past relief Of soothing 'tears'; cold anguish tied Him to the spot; his fingers still Closed on the dagger at his side; No prayer he dared to murmur as He looked up towards the crimson sky. A sudden flash, — then Mindia Sank down without a word or sigh. He lay upon the soft green grass; As if in slumber he reclined; Blood flowed in streams upon the ground And there the grass with blood was lined. The waning moon in sorrow gazed Upon the lifeless form below. She cast o'er him a silver veil And drooped her head in silent woe. The breeze came blowing down the steep, With silver moonbeams gaily played, Then for a moment stopped to gaze Upon the blood-stained deadly blade. It touched the unsheathed dagger's point, Whirled round the upturned fallen shield, Then flirted gaily with the grass And whistling danced across the field. |

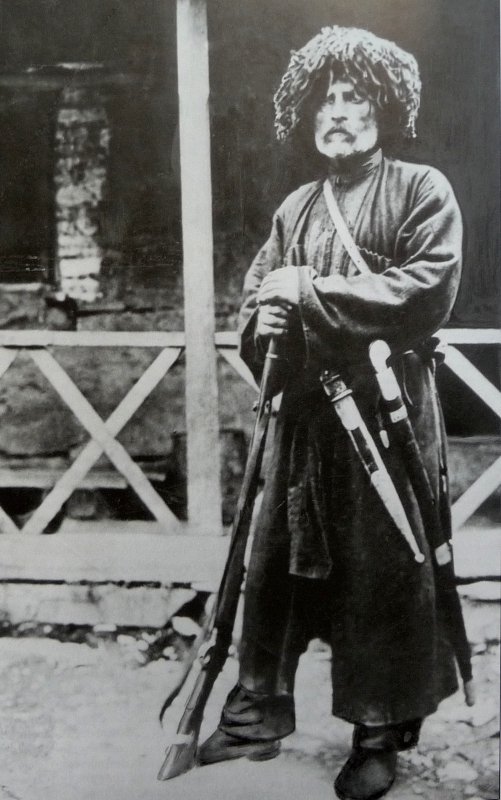

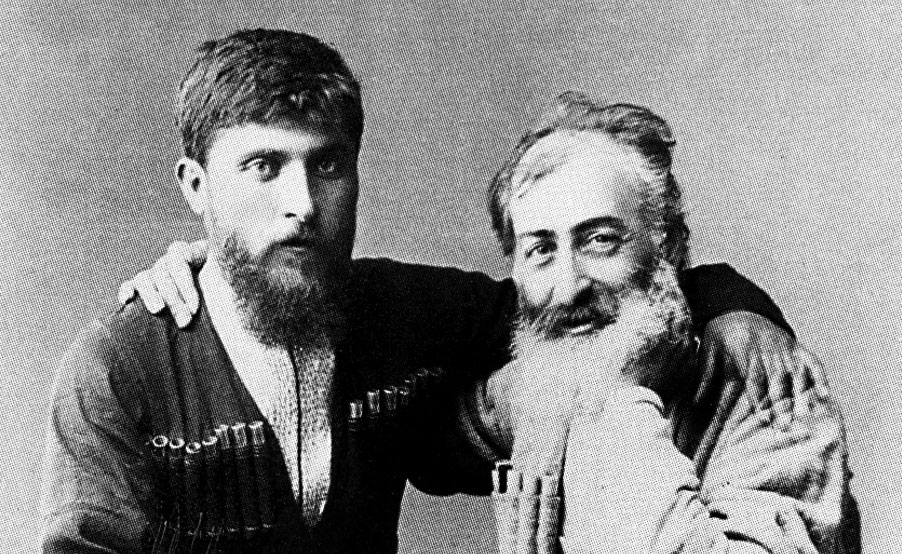

| Vazha-Pshavela (July 26, 1861-July 10, 1915) is the pen-name of the Georgian poet and writer Luka P. Razikashvili, a classic of the new Georgian literature. He was born in a small village Chargali (Pshavi mountainous province in Eastern Georgia) in a family of clergyman. He graduated from the Pedagogical Seminary in Gori 1882, where he became close to Georgian populists (narodniki). Then 1883 entered Law Department of St. Petersburg University (Russia) as a non-credit student, but returned to Georgia in 1884 due to financial restraints. worked as a teacher of Georgian language. He was also a famous representative of a National-Liberation movement of Georgia. Vazha Pshavela started his literature activities in mid-1880s. In his works, he portrayed everyday life and psychology of his contemporary Pshavs. Vazha Pshavela is the author of many world-class literary works - 36 epics, about 400 poems ("Aluda Ketelauri", "Bakhtrioni", "Gogotur and Apshina", "Host and Guest", "Snake eater", "Eteri", "Mindia", etc.), plays, and stories, as well as ethnographic, journalistic, and critic articles. He pictured the highlanders' life almost exactly ethnographically and still recreated an entire world of mythological concepts. In his poetry, the poet addressed the heroic past of his people and appealed to the struggle against external and internal enemies (poems A Wounded Snow Leopard (1890), A Letter of a Pshav Soldier to His Mother (1915), etc.). In his best epic compositions, Vazha Pshavela exposed the problems of interaction between an individual and a society, a human and nature, love and duty before the nation. A conflict between an individual and a temi (community) is depicted in epics Aluda Ketelauri (1888, Russian translation 1939) and Guest and Host (1893, Russian translation 1935); its characters choose against some obsolete laws of their community. The poet's preferences are strong-willed people, their dignity, and zeal for freedom. The same themes are touched in the play The Rejected One (1894). Vazha Pshavela idealized the Pshavs' old rituals, their purity, and non-degeneracy with the "false civilization". The wise man Mindia in the epic Snake-Eater (1901, Russian translation 1934) dies because he cannot reconcile his ideals with the needs of his family and society. The epic Bakhtrioni (1892, Russian translation 1943) narrates on participation of the Georgian highlander tribes in the uprising of Kakheti (East Georgia) against the Iranian subjugators in 1659. As a nature admirer, Vazha Pshavela knows no comparison in Georgian poetry. His landscapes are full of motion and internal conflicts. The language is saturated with all the riches of his native language, and yet this is an impeccably exact literary language. Thanks to excellent translations into Russian (by N. Zabolotsky, V. Derzhavin, B. Pasternak, S. Spassky, and others), Vazha Pshavela's compositions became available to representatives of other nationalities of the ex-USSR. Poems and narrative stories of Vazha-Pshavela have also been translated and published in more than 20 languages. Vazha Pshavela died in Tiflis on July 10, 1915. Buried ibidem, in the Pantheon of the Mtatsminda Mountain. |

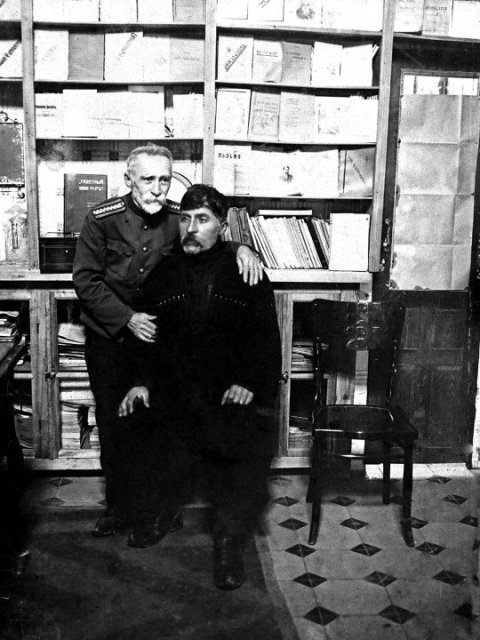

| Prince Alexander Chavchavadze (1786 – November 6, 1846) was a notable Georgian poet, military commander, and prominent public figure. Alexander Chavchavadze descended from the noble family elevated to the princely rank by the Georgian king Constantine II of Kakhetia in 1726. He was born in 1786, in St Petersburg, Russia, where his father, Prince Garsevan Chavchavadze, served as an ambassador of Heraclius II, king of Kartli and Kakheti in eastern Georgia. Tsarina Catherine II of Russia became a godmother at the baptism of infant Alexander, showing her benevolence to the Georgian diplomat. Alexander’s early education was Russian. He first saw his native Georgia at the age of 13, when the family moved back to Tiflis after the Russian annexation of eastern Georgia (1801).Aged 18, Alexander Chavchavadze joined Prince Parnaoz, the member of the dispossessed royal family, in the 1804 rebellion in the mountainous Georgian province of Mtiuleti against Russian rule. Following the suppression of the uprising, he was briefly put in prison where he composed his first literary works, including the first radical civic poem in Georgian, Woe to This World and Its Tenants. The poem quickly gained popularity, and brought to its young author a remarkable fame, his manuscripts widely circulating, his lyrics of love or protest, in the spirit of the 18th-century Georgian poet Besiki or of the French enlightener Jean-Jacques Rousseau, sung in Tiflis and elsewhere in Georgia. Following a year’s exile in Tambov, Chavchavadze reconciled with the new regime and entered a hussar regiment. Ironically, he fought in the Russian ranks under Marquis Paulucci when the next anti-Russian rebellion broke out in 1812 in Kakheti. In the same year, he married a Georgian princess Salome Orbeliani of the prominent noble family with family ties with the Bagrationi royal line. During the War of the Sixth Coalition (1813-4) against Napoleon I of France, he served as an aide-de-camp to the Russian commander Barclay de Tolly and was wounded in leg at the Battle of Paris on March 31, 1814. As an officer in the Russian expeditionary forces, he stayed in Paris for two years and the restored Bourbon dynasty awarded his service with a Légion d'honneur.Open to new ideas, in particular to the early French Romanticism, he was impressed by Lamartine and Victor Hugo, as well as Racine and Corneille, who entered Georgian literature through Chavchavadze. In 1817, Prince Chavchavadze became a colonel of the Russian army. Promoted to Major General in 1826, his military career reached remarkable achievement during the Russian wars against the Persian and Ottoman empires in the late 1820s. He was instrumental in liberating Armenian city of Yerevan from the Persians in 1827 and was appointed, in 1828, a military governor of the Armenian Military District. During the 1828-9 Russo-Turkish war, with a small detachment, he organized a successful defense of the Yerevan province against the marauding Kurds and surged into Anatolia, taking control of the whole pashate of Bajazet from the Turkish forces from August 25 to September 9 1828.[3] In 1829, he was dispatched as an administrator of the military board of Kakheti, where his patrimonial estates were located. Back in Georgia, Alexander enjoyed overwhelming popularity among the Georgian nobility and people. He was highly respected by his fellow Russian and Georgian officers. At the same time, he remained Georgia’s most refined, educated and wealthy 19th-century aristocrat, fluent in several European and Asiatic languages and with extensive friendly ties with the cream of Georgian and Russian society who frequented his famous salon in Tiflis. The prominent Russian diplomat and playwright Alexander Griboyedov married his 16-years old daughter Nino whom the famous Russian poet had tutored in music during his brief stay in Tiflis. Another daughter, Catherine, married David Dadiani, prince of Mingrelia, and inspired in Nicholas Baratashvili the hopeless love that made him the greatest poet of Georgian Romanticism. At his Italianate summer mansion in Tsinandali, Kakheti, he frequently entertained foreign guests with music, wit, and – most especially – the fine vintages made at his estate winery (marani). Familiar with European ways, Chavchavadze built Georgia’s oldest and largest winery where he combined European and centuries-long Georgian winemaking traditions. The highly regarded dry white Tsinandali is still produced there. Despite his loyal service to the Russian crown, Chavchavadze’s nostalgia for Georgia’s lost independence, monarchy, and the autocephalous church once again pushed him into rebellion, joining the 1832 conspiracy aimed at organizing a large-scale uprising against the Russian hegemony. The failed coup plot turned a disaster for the Georgian literature: most of his poetry written between 1820 and 1832, inspired by the pathetic Romanticism and egalitarianism, was burned by the author as possible evidence against him. He was sentenced to the five-year exile to Tambov, but the tsar, who needed his talents amid the ongoing Caucasian War, forgave him, however. Chavchavadze eagerly joined the expedition against the rebellious mountaineers of North Caucasus. Like his many fellow Georgian nobles, he found a good opportunity to take revenge for the permanent marauds organized by the mountaineers of North Caucasus on the Georgian marches in the past. He was promoted lieutenant general in 1841, and continued his service in the Caucasus, briefly as head of the civil administration of the region from 1842 to 1843. In 1843, he fought his last war, commanding a successful punitive expedition against the rebellious Dagestani tribes.Later, he was appointed a member of the Council of the Chief Administration of Transcaucasus. In 1846, Alexander Chavchavadze fell a victim to an acciden, under somewhat mysterious circumstances: while going back to his palace in Tsinandali at night, somebody from the near woods approached and splashed hot water while he was galloping on his horse. He lost the control of the horse and crashed into the ditch near by. He died from severe head injuries on the spot. Although the tragedy was most likely an accident, it has been rumored that he was killed by Russian assassins. He was buried at the Shuamta Monastery in Kakheti, Georgia. Chavchavadze was survived by a son, David, who was also Lt Gen in the Russian service during the Caucasus Wars, and three daughters, Nino, Catherine, and Sophia. Chavchavadze’s influence over Georgian literature was immense. He moved the Georgian poetic language closer to the vernacular, combining the elements of the formal wealth and somewhat artificial antiquated "high" style inherited from the 18th-century Georgian Renaissance literature, melody of Persian lyrical poetry, particularly Hafiz and Saadi, bohemian language of the streets of Tiflis and the moods and themes of European Romanticism. The thematic of his works varied from purely anacreontic in his early period to deeply philosophic in his maturity. Chavchavadze’s contradictory career – his participation in the struggle against the Russian control of Georgia, on one hand, and the loyal service to the tsar, including the suppression of Georgian peasant revolts, on the other hand – found a noticeable reflection in his writings. The year 1832, when the Georgian plot collapsed, divides his work into two principal periods. Prior to that event, his poetry was mostly impregnated with laments for the former grandeur of Georgia, the loss of national independence and his personal grievances connected with it; his native country under the Russian empire seemed to him a prison, and he pictured its present state in extremely gloomy colors. The tragic death of his beloved friend and son-in-law, Griboyedov, also contributed to the depressive character of his writings of that time. In his Romantic poems, Chavchavadze dreamed of Georgia's glorious past, when "the breeze of life past" would "breathe sweetness" into his "dry soul." In poems Woe, time, time, Listen, listener, and Caucasia , the "Golden Age" of medieval Georgia was contrasted with its unremarkable present. As a social activist, however, he remained mostly a "cultural nationalist," defender of the native language, and an advocate of the interest of Georgian aristocratic and intellectual elites. In his letters, Alexander heavily criticized Russian treatment of Georgian national culture and even compared it with the pillaging by Ottomans and Persians who had invaded Georgia in the past. In one of the letters he states: The damage which Russia has inflicted on our nation is disastrous. Even Persians and Turks could not abolish our Monarchy and deprive us of our statehood. We have exchanged one serpent for another. After 1832, his perception of the national problems became different. The poet unambiguously pointed out those positive results which had been brought about by the Russian annexation, though the liberation of his native land remained to be his most cherished dream. Later his poetry became less romantic, even sentimental, but he never abandoned his optimistic steak that makes his writings so different from those of his predecessors. Some of the most original of his late poems are, Oh, my dream, why have you appealed to me again, and The Ploughman written in the 1840s. The former, a rather sad poem, surprisingly ends with hope for the future in contemplation of the poet. The latter combines Chavchavadze’s elegy for his past years of youth with calm humorous farewell to lost sex-life and potency. Chavchavadze also composed a historic work, "The Short sketches of the history of Georgia from 1801 to 1831." O Love Divine! O love! O mighty love! your power enslaves and holds the heart in thrall. Even monarchs bend their knees to you, and on your shrine prostrating fall. Exquisite pain, exquisite bliss and passions sweet the heart o'erflows, So, can you blame the nightingale that pours love's essence o'er the rose? O love! your fires inspire the souls of all created 'neath the sky; Adored are you by great and small, by gallants, kings and gods on high; Where'er you go a throne awaits you decked with tears and sweet delight; You are the lord of hearts impassioned; all fall 'neath your conquering might. Has ever slave thus bound to you, thus fettered down, for freedom pined Though wild desires invade the heart and madness penetrates the mind? Though passions make me nigh expire, let ecstasy of love be mine; And let me live or die for you, your willing slave, O love divine! |

|

Unknown author, XIX |